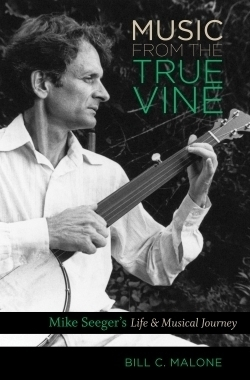

Music From the True Vine

Mike Seeger's Life and Musical Journey

To a large segment of Americans, the Seegers have been as culturally important as the Gershwins—and there were more of them. In fact, two of that artistically fecund tribe were still producing music as of last October. The most famous of these, of course, is folksinger and political activist Pete Seeger. The other is Peggy Seeger, also a songwriter and folksinger and widow of Scottish singer Ewan MacColl. Then, there is Mike Seeger, the subject of this book, who died in 2009. He and Peggy are Pete’s half-brother and sister. The patriarch of this musical clan was Charles Seeger (1886-1979), a classically trained musicologist with a taste for American vernacular music and radical politics. His two wives, Constance (Pete’s mother) and Ruth Crawford Seeger (Mike’s and Peggy’s) were both respected musicians as well.

This background helps explain why Mike Seeger became one of the most dynamic and influential figures in the folk music surge of the 1950s and ’60s and an ardent preservationist and performer of music from southern Appalachia. Although he was never as politically outspoken as Pete, Mike, like his father, was a war resister, and a conscientious objector during the Korean War. In Bill C. Malone, Seeger has a biographer worthy of his importance. Malone is generally regarded as the first serious scholar of country music, largely owing to his trailblazing 1968 tome, Country Music U.S.A.

Seeger developed a taste for the brand of country music now called “bluegrass” at least as early as 1952, after he had forsaken his guitar lessons to learn the banjo, an instrument with which Pete was already internationally identified. That same year, Mike saw Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs and the Foggy Mountain Boys perform, which he described as “near about to a religious experience as I’ve ever had.” While serving as a kitchen orderly at hospital near Baltimore from 1954 to 1956 to fulfill his obligations as a conscientious objector, he became a friend and picking buddy to many of the white Southerners who had immigrated to Baltimore after World War II to find work. One of these was Hazel Dickens, the mournful sounding and fiercely feminist coal miner’s daughter from West Virginia. The two would perform and record together intermittently for the rest of Seeger’s life.

Malone chronicles Seeger’s co-founding in 1958 of the New Lost City Ramblers, arguably the most authentic exponents of the rural string band styles of the 1920s and ‘30s; his development as collector and recorder of folk music; his emergence as a solo recording artist and international troubadour; and his significance as a instructor of instrumental folk music techniques through tapes and DVDs. “There are many ways to measure Mike’s legacy,” Malone observes. “But above all, one sees the fulfillment of his dreams in the young musicians, both famous and obscure, who keep the music alive.”

Reviewed by

Edward Morris

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.