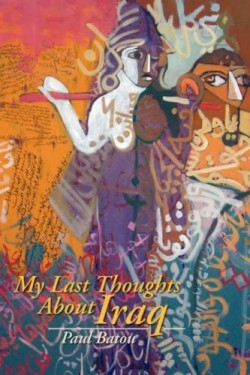

My last thoughts about Iraq

Batou’s book is one of longing, for a lost civilization, a dispersed people, an ancient beauty still moldering under the remains of Baghdad. These poems might easily be characterized as extended lament. Batou approaches them from multiple perspectives, from lost son to gypsy guitar player, but in all of the poems, loss figures prominently as it has for thousands of years in the region.

Batou approaches his subject in many ways, through music, painting, and words. He carefully introduces the circumstances from which modern Iraq has evolved, then offers reproductions of his paintings so that readers might experience the turmoil in a new way. The book then makes its way into poems which take place both in Iraq and in the United States where Batou has made his life. Readers are left with the impression that he never fully integrated into American culture—he is still an Iraqi at heart.

Many of the poems in this volume cover the same territory, laments to God over what has been lost, ruminations on the glory that was, prayers for what might be. He writes of isolation in “Journey with Ishtar”: “We live as strangers in different lands. / We live as drunks with no alcohol.” Batou likens himself to the gypsies, forever wandering, forever singing his lament. He mourns in “Iraqi Freedom,” “My sadness is written on rocks and clay, / Placed in museums around the planet. / My stories and sadness were stolen by strangers and thieves.” Batou tries to explain the devastation wrought by the Iraqi war. He urges his readers to remember with him the songs of folk singers, the ease of the elderly resting in the shade, the joy of a new bride.

While initially the poems have persuasive, mournful power, the edge is dulled by repetition. Rather than delving into new ways to figure the city and her history, Batou sticks to a few central images and ideas: tiny villages, simple suffering people, spiritual lands. In creating images, the poet might further explore the power of figurative language. With a history as rich as Mesopotamia’s, Batou has innumerable options for language, allusion, and image, but he fails to mine it as fully as he might. He lingers too long reestablishing loss in every poem. He would do well to trust the progression inherent in a volume, and build on the history and long literary tradition of this place he so loves.

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.