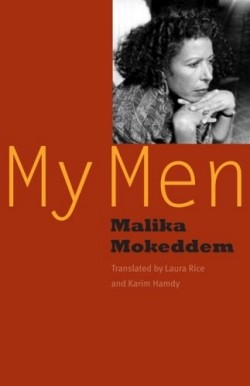

My Men

The title of Malika Mokeddem’s memoir may puzzle those familiar with the author. Written by one “whose only religion is the right to equality, to freedom, to love, to sexual choice”—a stance which vehemently de-fends autonomy—the possessive title seems incongruous. But part of Mokeddem’s intricate purpose is to revise what it means to claim another human—in oppression, erotic romance, writing, and familial relationships. Mokeddem herself boldly claims successive lovers as homage to her own freedom. She writes of how they have shaped her, while she possesses her selfhood. Each chapter is devoted to at least one masculine shaping force, but the narrative is her own.

My Men was written with many purposes: to needle those of dissenting opinions, to save herself “from the aimless wandering of total freedom,” and to dispel silence. In the last chapter, we learn of another purpose for the book: “I often have the feeling that I celebrate here the woman I was back there who battled against so many difficulties with nothing more than her rage for life.” The book begins and concludes symmetrically with mis-sives—the first to her father and the final to a future lover— to express what two men cannot hear.

This work came into being by prestigious means. It received support from the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Cultural Services of the French Embassy in the United States, along with the National Endowment for the Arts. It is the third of Mokeddem’s books released by the University of Nebraska Press and the second Laura Rice has translated.

Erotic and alimentary, Mokeddem’s nonfiction writing owes much to the seemingly transparent conveyance of her thoughts. She writes of her corporeal urges and emotional conditions as if living them out by her pen. The book is a narrative of self-discovery. Yet it is not an example of the solipsism which is incurably inappropriate in the current global social climate. Instead, it delves into one of our current crises—institutionalized and systemic patriarchy. Although the author offers many aphorisms that will likely outlive her—“love is a cannibal delight,” for in-stance—Mokddem refuses an easy politics. In this, the book belongs near those of Gloria Anzaldua, Adrienne Rich, and Gloria Steinem.

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.