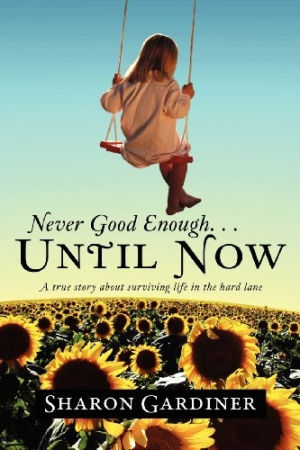

Never Good Enough Until Now

A True Story about Surviving Life in the Hard Lane

Acknowledging childhood trauma is important, but identifying the problem is often not enough to help people move beyond the pain. In her midlife memoir, first-time author Sharon Gardiner tackles both the benefits and the shortcomings of this type of self-reflection. Gardiner grew up in an abusive family and attributes her survival to both recognizing the abuse and questioning the irrational beliefs and dysfunctional behaviors she learned as a child.

Gardiner writes in an earnest, first-person voice and heads each chapter with inspirational quotations from sources like Marianne Williamson’s A Return to Love and Louise L. Hay’s You Can Create an Exceptional Life. The quotes suggest a New-Age point of view, but Gardiner delivers the hard-won experience of a divorced Australian mother working the very down-to- earth jobs of police officer and emergency-room nurse.

Growing up in an abusive, alcoholic home, Gardiner did not really comprehend that her environment was dysfunctional. It seemed normal. Now that she understands how damaging her childhood was, it appears she wants to shout her realizations from the rooftops. Her enthusiasm turns into melodrama at times. She is prone to making sweeping statements that claim dramatic transformations, but fail to consistently provide the supporting details.

When she does examine the particular moments of her life, Gardiner’s story comes alive. For instance, she takes readers right to the edge of her suicidal impulses by describing very specific thoughts and using evocative imagery. At other times, though, one is left to wonder exactly what happened. Why is she out of touch with her brother? How did she break away from the abusive relationship with her mother? Relationship issues often receive only cursory examination.

Gardiner seems comfortable confessing her personal mistakes, such as admitting when her drinking gets out of control. But she does not reveal much about her connections with others. This can lead to apparent contradictions in her narrative, like her strongly declared devotion to raising her children coupled with her almost continuous absence from their daily lives. Given the self-reflective nature of much of her writing, it is surprising when Gardiner chooses not to deeply address interpersonal concerns.

Mechanical missteps sometimes distract from Gardiner’s story. The liberal application of commas overwhelms many sentences, and occasional misspellings are distracting. Her use of words like “orientate” and “disorientate” seem jarring at first, but eventually become part of Gardiner’s particular Australian voice, as she takes us through the streets of downtown Sydney.

Imagery is Gardiner’s strong suit, and she frames her story of reinvention with the image of a swing that is a dizzying place for her young self, but becomes liberating several decades later. The cover art, a high-flying swing soaring above a field of sunflowers, reinforces Gardiner’s positive outlook.

Reviewed by

Sheila M. Trask

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.