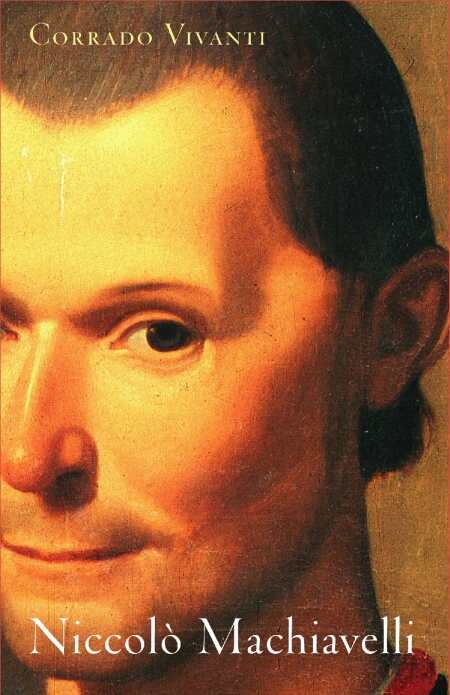

Niccolo Machiavelli

An Intellectual Biography

Machiavelli scholar paints a complex picture of the circumstances that shaped the man whose name became synonymous with political cunning.

The term “Machiavellian” has established itself as a synonym for use of cunning and deceit when seeking to gain or preserve political power.

While people may be familiar with Niccolo Machiavelli as the early sixteenth century Italian statesman and author of The Prince, a guide to the use of power, less is known about the man himself in the context of his copious writings and letters. Delving minutely into these writings, noted Machiavelli scholar Corrado Vivanti paints a complex picture of this man’s life, thoughts, and relationships, as well as the turbulent times in which he lived and the political circumstances that shaped his writings.

Starting at age twenty-nine, Machiavelli, as a statesman and diplomat representing Florence’s interests, and as a military leader charged with preserving Florentine authority, came to understand the importance of shaping Italian life principles in order for his people to survive in an increasingly complex Europe. As the author explains, “The aim of this book is to gather together the nexus between these activities and Machiavelli’s works, which quickly became fundamental to understanding the fortunes of men grouped in political societies.”

But as the biography’s subtitle suggests, this book is more of an examination of the cerebral side of this statesman and his political world of scheming authority figures and rival states within Italy and beyond, an oftentimes brutal classroom. And perhaps it is just as well. As the author points out in the chapter titled “A Shadowy Period: The First Half of His Life,” not much is known about his life before he became secretary for the chancery of Florence.

Early in a young Machiavelli’s reign as chancellor of the Florentine Republic, his astute ability to tactfully persuade functionaries to do his bidding becomes apparent. And, as the author notes, the end result is that they become his supporters.

The author writes, “Right from the early days of Machiavelli’s post as secretary, these men showed their affection for him, which demonstrates that he had organized their work in a manner that transformed his subordinates into friends: they joked freely with him, and when he was far away from Florence sent him missives in which, together with news and matters concerning the chancery—often cloaked in heavy and sometimes scurrilous witticisms—there always resounds the request to receive their letters and the exhortation to return as soon as possible.”

The author’s analysis of his subject is highly detailed, suited for the serious reader. The appendix is actually an esoteric and heavily referenced essay, “Notes on the Use of the Word Stato in Machiavelli,” stato referring to government. And his notes—references and attributions to the works of other scholars of historic Italy and Machiavelli—run thirty-six pages.

A reader having a solid grasp of Italian history, particularly that of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, will likely embrace this biography. But a reader seeking a general picture of Machiavelli’s personal life, family, and personal growth is better served by starting elsewhere first.

Reviewed by

Karl Kunkel

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.