Northwoods Auto Repair

Fix your car without any tools or supplies - just by sheer force of mind

These quick bursts of cracked brilliance, these splintered bedtime stories for grown folks, have the power to make readers laugh, and then think… Then scoff at the futility of thinking.

The lineage for this spirit of irony traces through close style-relative The Stinky Cheese Man (1992), and shares genes with the disguised commentary of Shel Silverstein and Ogden Nash.

The narrative is punctuated by satirical jabs at easy targets: fascists, revolutionary Marxists, grumpy old people. Soling reaches beyond the stock material of political ideologies and good-naturedly smears less obvious interest groups, from Philip Glass fans, welfare children, and disco music, to individuals named Greenspan, civil servants, druggies, advertising pushers, and those who covet a handicapper parking permit but cannot qualify.

The hero (if any) in The Disciples of Trotsky is a lumpy blue creature with the misfortune to have an enchanted pickax lodged in the back of his head. He’d ask someone to remove it but, “…if anyone were to remove the pickax from Sniffles’ head they would instantly / [Perfectly placed page break] become French.” Sniffles’ best buddy has a similar weapon caught in his forehead; he’s hating life even more.

A whiff of George Orwell’s Animal Farm blends with Shrek-variety fairy tale character kingdoms. The seven dwarves, except for Grumpy the nihilist, are displaced by cheaper migrant labor and spurred to become outspoken radicals. “‘We were just pawns for the fascist regime of Prince Charming,’ Happy added. ‘We satisfied his hedonism with our sweat and toil.’”

The Bomb That Followed Me Home is told from the point of view of a boy trailed by a stray bomb, which is spoken and thought of as a dog. It’s very possible that there is symbolism at work here. The boy begs his mother to keep it, but she knows the way kids are, and doesn’t want to get stuck guarding it all the time. This book’s spotlight is decisively won away by the sour and cantankerous Mrs. Greenspan, a next door neighbor who shrieks incoherencies, which the boy divines by repeat experience to mean things like “‘Get off my lawn! I am completely unstable and might burst a blood vessel in my brain!’” The boy tries to feel sorry for her husband, but Mr. Greenspan is—let’s face it—quite the asshat himself.

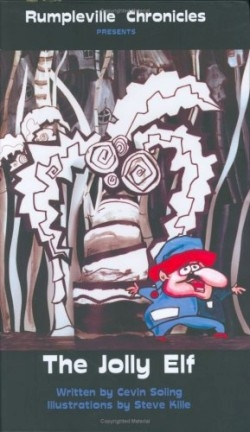

Save The Jolly Elf for last, or better yet slip a copy to a friend with no explanation. The opening reads sedately, but Soling lowers the boom, and suddenly the overturned tale is an allegory for the worst of impulses. The Jolly Elf ends falsely, followed by a two-line story called “The Adventures of Waldo.” Waldo is identified as a lump of mud stationed by a sink drain, but he is clearly a wad of hamburger, which messes up a bluntly morbid joke. On the following page the title story resumes, arcing to a cynically inevitable conclusion.

The evil geniuses behind these high concept subversive fairytales met in the downtown New York music scene. The author is an independent film producer, maker of the anti-propaganda sketch comedy The War on the War on Drugs.

The illustrator’s steady gig is playing bass and sitar in Dead Meadow, a national psychedelic band. Kille’s artwork both feeds from the text and reinforces the wamperjawed consciousness with curvilinear houses and a penchant for benign distortions. The extent of common understanding between these creative professionals is evident.

This even-quality, well-conceptualized series is all about fun, but certain ghoulish gags could startle youngsters and these look like normal children’s books on first inspection. The derivative components are forgivable borrows refreshed by innovative recombination.

In Soling and Kille’s blenderized stories, faulty pieces of the twenty-first century break off and fall into an imaginary medieval milieu, where they fit surprisingly well. The Rumpleville Chronicles are sardonically elegant stuff. You can’t read just one.

Reviewed by

Todd Mercer

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.