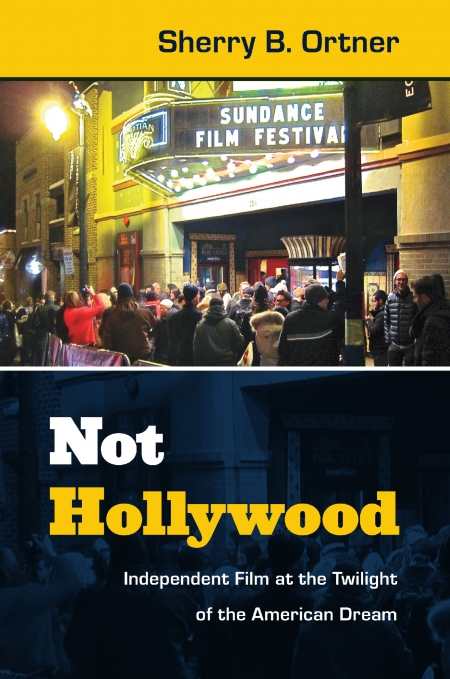

Not Hollywood

Independent Film at the Twilight of the American Dream

There is a glut of books published on all aspects of film studies: critical analyses of directors’ oeuvres; in-depth explications of classic and contemporary films; film genre readers; and histories of cinema in scores of countries and regions. All of these are written by scholars in the field of film studies. What makes Not Hollywood so refreshingly different and incisive is that the author knows very little about film in any academic sense. Sherry B. Ortner is an established anthropologist who has published numerous books considered seminal works of research in that field.

Not Hollywood, then, is a cross-disciplinary study of what exactly it means to be an American Independent film or filmmaker in the late twentieth/early twenty-first century, under the looming economic shadow of Hollywood. Ortner doesn’t critique the independent films that she discusses in this book; instead, she looks for a cross-section of response to the films across the divides of class, race/ethnicity, age, and gender.

Ortner, in talking extensively with directors, producers, critics, and filmgoers, paints a picture of the independent film scene as being mainly concerned with portraying a “true” or “real” picture of modern life. By contrast, “Hollywood” films are typically beholden to stockholders producing films that satisfy focus groups and guarantee audiences a certain feeling of safety and a happy ending. She notes that many young independent filmmakers (she focuses on Generation Xers) feel hostile towards the Hollywood culture, which largely registers ambivalence toward the independent scene, and, in fact, has at times put some of its enormous capital toward developing smaller offshoot studios designed to produce the very independent films that the embattled underdog auteurs have fought to bring to fruition.

Ortner comes to general conclusions about these types of hostilities and hard feelings by noting how many times phrases like “I hate Hollywood,” or “Hollywood is crap” are uttered among members of the “indie” film culture. She proceeds from this so-called “discourse analysis” (careful to frame it in the context of linguistics rather than ethnography) to consider dozens of independent movies produced from 1990 to the late 2000s.

By analyzing the basic plots and characteristics of these independent films (a chapter is devoted to the particularly “dark” ones, though it is noted that almost all independent films have a grittiness that is absent from many Hollywood-produced films), Ortner is able to show how independent film in America can shine a light on the various problems faced by the Gen X population—most notably and extensively post-9/11 immigration issues.

There is much information to be gained from Ortner’s expert use of anthropological methodology to explore the culture of the culture of independent cinema. Film scholars are often too close to their material to obtain findings anywhere near as striking and engaging as the ones enumerated in this volume.

Reviewed by

Daniel Coffey

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.