Not Quite a Judas

The story of boys who become fast friends in peacetime only to find themselves adversaries once war breaks out is a tale that has been told many times, but rarely so believably and authentically as Philip Baker does in his World War II tale, Not Quite a Judas. The English author draws deeply on his memories of growing up in Britain during the war, as well as his own military service. He gives his book such a true-to-life feel that readers will find themselves double-checking the author’s notes to see if Baker’s story, as related by an old man to his grandson, really is a work of fiction.

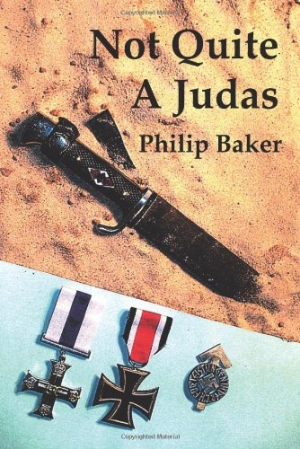

The wealth of detail Baker has put into the character of his narrator, John Hardwicke, is matched page for page by the research he has done to ensure that John’s friend, German Erich Falkenberg, is equally lifelike. Baker is a collector of Nazi memorabilia and the author of a three-volume set about the Hitler Youth. He has used his knowledge to recreate for the reader what life was like for young men in Germany in the years immediately prior to the start of the war. Adding illustrations from his collection not only enhances Not Quite a Judas, it also further adds to the reader’s wonder at just how fictional these characters really are.

The first half of the novel is a delightful story of two teenagers, one British and one German, who become friends while living with their fathers in the Persian Gulf in 1936. But it is also fraught with foreboding. The boys go to Germany to visit Erich’s grandparents in Nuremberg, where they witness one of the huge Nazi rallies for which the city later became infamous. John returns the favor, inviting Erich to spend time with his grandparents on the south coast of England, and the next year Erich invites John back to Germany to spend the summer camping with the Hitler Youth. This all happens beneath the shadow cast by Adolph Hitler, so readers know what the boys do not seem to know: Their friendship will be tested when they find themselves on opposite sides of the war.

John’s story is related by him to his grandson some sixty years later. To tell the rest of Erich’s tale, Baker has to shift voice, and that does become a bit disconcerting, especially when the author intersperses John’s narration with his own narrative of Erich’s service in the German Navy. Baker sets the stage for their eventual confrontation early on in the novel, and while their reunion is a bit contrived, it is neither unexpected nor forced.

What happens between and to Erich and John makes for an excellent, entertaining, and thoroughly believable story. At times, readers may feel as if they are watching a 1940s, black-and-white movie rather than reading a novel, but that’s a good thing, especially for fans of British movies from that era. The author captures the mood and banter of the period, and he artfully presents it in a way that both educates and entertains.

Reviewed by

Mark McLaughlin

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.