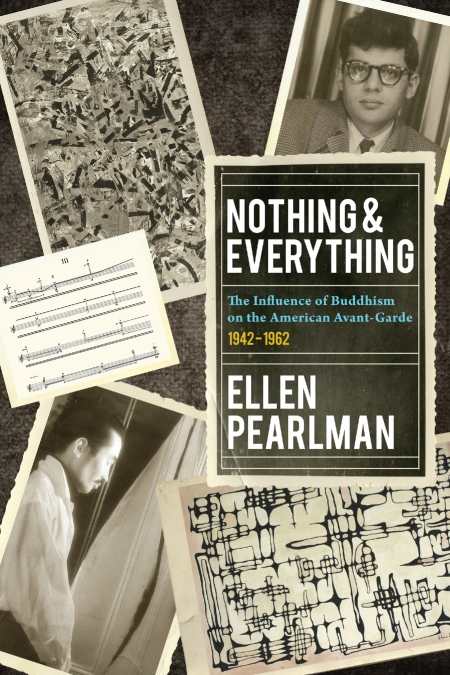

Nothing & Everything

The Influence of Buddhism on the American Avant Garde

Into the ancient pond / A frog jumps / Water’s sound!

This haiku by Japanese poet Matsuo Bashô, is perhaps the most famous in all of Japan. Although this translation by Zen teacher D.T. Suzuki was not the first, Suzuki’s work in bringing the teachings of Buddhism to the west is not unlike a stone—or frog—plunked into an old pond. The sound of his splash, and its subsequent echoes, marked such artists as John Cage, Meredith Monk, Jack Kerouac, Jackson Pollock, Franz Kline, and others, who in turn influenced countless more. The impact of Buddhist thought and Zen practice on intellectual and artistic communities is now everywhere apparent, but Pearlman’s book, Nothing & Everything, explores the point of origin and its rapid development in the American avant-garde.

How to trace the exponential impact of such a force? Pearlman divides her book into six parts, each focusing on particular persons or areas of impact. She begins with the life and work of D.T. Suzuki, progressing in the second part to the composer John Cage. She chronicles the creation and impact of Cage’s major works, his influence as a teacher at Black Mountain College, and his collaborations with and influence on such artists as Merce Cunningham, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Allen Kaprow, and Alison Knowles. The third section focuses on Happenings, Fluxus, and the Judson Church in New York City.

In subsequent parts, Pearlman continues to explore the waves of influence begun by Suzuki’s appearance in New York in 1952. She chronicles the formation of The Club, “where critical dialogue and its eager audience convened.” This hothouse of artistic discourse included New York School poets John Ashbery, Barbara Guest, and Kenneth Koch, as well as composers, artists, and philosophers Joseph Campbell, David Smith, Isaac Lassaw, Robert Motherwell, and others. In the fifth part, Pearlman glances back at the impact Zen-influenced American artists had on their Japanese counterparts, exploring the relationships between Saburo Hasegawa, Isamu Noguchi, and Franz Kline; and in the sixth she considers the Beat writers, particularly Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg.

Though occasionally difficult to follow chronologically, Pearlman’s book works to trace the rippling, whirling influences of Buddhism on some of the most important American artists of the twentieth century. She describes groundbreaking performances, the cross-pollination of the European Dadaists, and the particular Buddhist principles that resonated most deeply with American artists. Artists, avant-garde aficionados, and those interested in the influence of Eastern thought on the West will be thankful to Pearlman for tracking and cataloguing the leaps that made the splashes that cocreated avant-garde.

Reviewed by

Jennifer Sperry Steinorth

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.