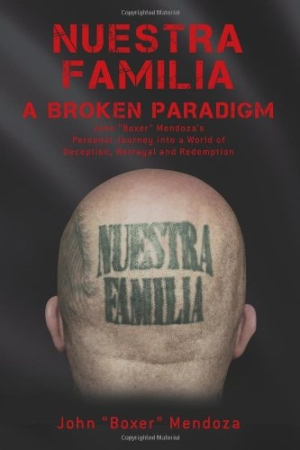

Nuestra Familia - A Broken Paradigm

John "Boxer" Mendoza's Personal Journey into a World of Deception, Betrayal and Redemption

Reading a memoir of a prison gang member is unusual fare for those completely unfamiliar with the correctional system of the United States. Violence? Check. Drugs? Check. Odd Nicknames? Check. Girlfriends? Check. Illegitimate children? Check. Nuestra Familia - A Broken Paradigm, by John “Boxer” Mendoza, has all that and is a comprehensive look at the psychology of gang life.

Mendoza became a career criminal at the age of twelve, when most boys are playing video games, kicking a soccer ball, and beginning to think about girls. He wields a gun, robs houses, and has his first taste of heroin in the San Francisco Mission District. He is in prison before he is old enough to drink.

The Nuestra Familia (NF) was founded in 1968 in response to crime and prejudice against Hispanics (primarily Mexicans) living in California. The author provides an extensive history and recounts the fourteen laws of the NF. Mendoza bought into the original cause and was a superb student of the gang’s tenets and constricting rules. He waged war on his perceived enemies and “earned” money for the NF in and out of jail, but his loyalty bought him nothing after twenty years. When the cause became money instead of human rights, Mendoza “defected.”

The text is eloquent and loaded with words that leave one to wonder how the author acquired his language skills. There is no mention of any education prior to prison or of reading in the library while serving his sentence. Words such as “ameliorate” and “internecine” nudge up against the basest gang-speak—having an Urban Dictionary at hand is helpful as not even contextual reading can make sense of some of the slang.

More than three hundred pages are devoted to Mendoza’s actual time in prison, yet this portion of the text is dry and provides little insight. Readers will likely be expecting this section to include day-to-day experiences and emotions, but the tone is matter of fact, and the extensive list of names, gang affiliations, and military-like titles seems without end. One wants to feel sympathy for Mendoza and others who are and have been in his situation, but, unfortunately, the writing does not elicit much emotion.

There are, however, brief moments when Mendoza’s own emotions peek through what feels like his granite exterior. His wife, Vicki, suffers from Lupus and a heart ailment. She is briefly mentioned in the first chapter or two but does not return until page 385 when Mendoza writes of her early death at the age of forty while he is still behind bars serving what may be a life sentence. Here Mendoza finally breaks down, noting that he is now “devoid of purpose” because he has lost the one person he loved. Similar sentiment is visible when Mendoza’s mother and then grandmother die while he is imprisoned.

Mendoza’s purpose in writing Nuestra Familia is to “deglamorize” the gang lifestyle, and he accomplishes that goal. He writes, “Hopefully, my experiences and the things I’ve exposed in this book can succeed in changing just one life. If I’m able to accomplish this, then all my labors and efforts have served an even bigger purpose.” The work is an apt read for high school students in inner cities—where gang activity is rife to catch them—before they make an irreversible mistake. It is also an intriguing read for viewers of shows like Lockdown on the National Geographic Channel and Gangland on The History Channel.

Reviewed by

Dindy Yokel

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.