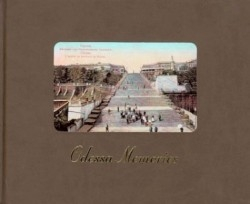

Odessa Memories

“To live like God in Odessa-the golden city, the jewel of the sea.” Such were the hopes and praise drawn by the city of Odessa of the southern Ukraine. Few if any cities could rival pre-revolution Odessa for ethnic diversity, intensity and colorfulness of life, civic progress, economic vitality, or cultural riches. From its foundation in 1794 by order of Catherine the Great, Odessa was on a constant trajectory of growth and enhancement until the cataclysm of the 1917 Revolution and its aftermath slowly and brutally ended its near-autonomy. This book of essays in album format offers a brilliant tribute to the proud seaport city in its heyday, flourishing at the farthest margin of Europe.

Odessa, perched on the Black Sea’s northwestern shore, might be deemed too distant, too exotic to be of mainstream interest. Such a claim cannot be sustained while the literary talent of Aleichem, Babel, Kuprin, and Paustovsky nourish the reader’s mind; while the musical genius of Oistrakh and Gilels reward the listener’s soul; and while the lives of Pushkin, Gogol, Gorki, and Bunin fire the imagination. All had powerful ties to Odessa. Nor should the history of Odessa be neglected while contemporary cities seek enlightened civic leadership, effective philanthropy, and successful social integration.

The book, which combines rare historical images with cultural-historical narratives, is well served by its contributors. For the editor, a Guggenheim Foundation specialist in cultural exchange with Russia, collecting Odessiana runs in the blood; rare posters, postcards, and portraits from his collection provide a rich visual history.

Patricia Herlihy, professor emeritus of history at Brown University, and author of Odessa: A History, 1794-1914, contributes an essay that moves from politics and economics to personalities and projects. She describes the brilliant city chiefs of early Odessa-larger-than-life personalities of international backgrounds, including Don Joseph de Ribas, a visionary Spanish-Italian soldier of fortune; De Volant, a practical Dutch military engineer; the Duc de Richelieu, a proven general and administrator, the Comte de Langeron, a gifted trade negotiator; Count Vorontsov, a cultured Anglophile; Count Stroganov, an improver-educator; and General Kotsebu, a force in railroad development. All were fortunate in that the city’s leading Greek, Armenian, German, Italian, Jewish, and Russian citizens were remarkably keen to endow hospitals, schools, libraries, public gardens, and other amenities.

Oleg Gubar and Alexander Rozenboim, both long-time residents of Odessa, supply a comprehensive essay on work, leisure, recreation, and cultural pursuits from the city’s foundation to its World War II experiences.

Despite enlightenment at the top, “everyday life” (particularly at the bottom) was never an unbroken golden dream. Early Oddessans faced many challenges, among them a tough climate, isolation, and limited supplies of food, fuel, and water. Cholera epidemics struck periodically; worse, pogroms took hundreds of Jewish lives in 1821, 1871, and in the black year of 1905. However, what resonates in the Gubar-Rozenboim essay is the capacity of the numerous ethnic groups to coexist, work, and develop enterprises ranging from exporting canned fish to importing opera troupes. They do full justice to the city’s markedly rich and multiethnic cultural life, in which the large Jewish community made outstanding contributions in music, theater, literature, and film, producing some early masterpieces. (The city claims to be the birthplace of cinema, citing the pioneer work of Iosif Timchenko in 1893.) The stellar names of Babel and Eisenstein command the forefront, but the authors confirm that a galaxy of varied artistic talents held Odessans spellbound.

Implicit in the essays in Odessa Memories is the city’s determination to want for nothing that reflected progress and sophistication. Citizens recognized that this goal required committed leadership and continuing public participation-a conscious will to self-improvement. Significant crime and corruption did co-exist with civic progress, and the book does not neglect them. Mishka Yaponchik (the real-life progenitor of Isaac Babel’s Benya Krik), his strong-arm gang, and their goings-on appear in text and illustration.

The publisher has produced an exemplary volume, reflecting exceptional qualities of design, illustration, printing, and binding. Beginning with the color postcard of the famed Potemkin Steps, inlaid into the fine faux morocco front board, the book goes on to excel. The layout, which juxtaposes double-page color spreads with small black-and-white photographs, is dramatic and engaging, and the selection of images is outstanding. Thanks are due to Antonina Bouis for fluent translations.

Odessa Memories is unique; the bibliography lists no English-language forebears that bring Paris-on-the-Black Sea to the reader. Fortunately, in addition to Aleichem and Babel, the bibliography brings Paustovsky and Olesha to the reader’s attention. In all, this is a book to treasure.

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.