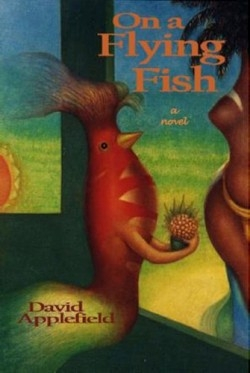

On a Flying Fish

Brave indeed is the novelist whose gregarious, anxious, polyglot alter-ego (yes, his name is Ernest) dares to anatomize—even celebrate—that peculiar inertia of beginning to write. In this novel, inspiration eluding the narrator in his sterile publishing job in New York and a torpid love affair in Frankfurt, with typewriter packed, he flees to a nondescript Caribbean island where he witnesses the murder of a rather witless shaggy dog story of an ex-pat.

It’s enough to bring cork-lined bedrooms back into fashion.

Nor is it entirely without risk for said narrator to repeatedly interrupt his story to muse on composition in general, even to plead directly to his putative readers and reviewers for consideration of literary merit. So much of the writerly life is mood. That said, the reflections are an almost welcome respite from the lukewarm patois of an island roman policier, for in imagining a dialogue with his faceless audience, asking that his words engage their imagination, for all its self-regard, it is also plaintive, taking him to what is his ultimate theme and concern: that searching for a voice, inventing a style, that all novel-creating ultimately is.

“It’s that process of filling in that I want the novel to oblige readers to follow… therefore I offer only half-stories, pieces,” he says. “Scream ‘not fair’ or ‘artistic incompetence’ or ‘boring’ and I’ve succeeded in moving you off-center… I’ve created a conscious reaction and have thereby proved something.”

The author’s verve of language, his relish of engaging the maddening daily noise of the world, is in perfect pitch. Even his beloved Lab’s animal antics steal the scene, written in great comic strokes. If only the girlfriend, the “she” who is given no name and precious little French dialogue, could have held her own with his masculine pre-occupations.

The author has spent nearly twenty-five years in Paris as a bilingual French-English source, a writer of guidebooks, and a lecturer on contemporary culture at the Institut d’Etudes Politiques de Paris. This is his second novel, following Once Removed; his next will be set in the Ukraine. He may be in the midst of some cultural lag. True, France is a nation that reveres the vocation of writing, from Montaigne to Proust: one’s writing is a reading of the self, the ultimate confessional. But self-reflection, mirror to mirror, can also be blinding. (August)

Leeta Taylor

Reviewed by

Leeta Taylor

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.