On Cold Iron

A Story of Hubris and the 1907 Quebec Bridge Collapse

On Cold Iron is an outstanding historical and technical study of an avoidable human tragedy.

On Cold Iron, Dan Levert’s history and critique of the 1907 collapse of the Quebec Bridge, starts with an extended account of the Ritual of the Calling of an Engineer as a reminder of an engineer’s obligations. Nobel Laureate Rudyard Kipling designed the ceremony, including its solemn oath and bestowal of iron rings.

The structural failure of the huge iron bridge claimed 76 lives, some of whom were trapped in the wreckage and drowned as the tide crept in. Since it was first performed in 1925, more than half a million Canadian engineering graduates have been “Obligated, on Cold Iron,” and Levert’s analysis details why this ritual is so “uniquely Canadian” and so meaningful to the country’s engineering profession.

The bulk of the book concerns the design and construction of the Quebec Bridge, which was ultimately completed in 1917 (though tragically not without another fatal major accident), and which still remains the longest cantilever bridge in the world.

Plans for a bridge to connect historic Quebec City across the St. Lawrence River to railroad connections had begun as early as 1851, but the river’s daunting cliffs, tidal changes, ice jams, and maritime traffic were formidable technical challenges. No bridge had yet been designed or built to span 1,800 feet, and the costs were judged too great to proceed. It wasn’t until 1887 that a private Quebec Bridge Company was created, supported by generous governmental subsidies, and plans were developed for this unprecedented construction project. It was hoped to be finished in time for the Prince of Wales to be able to stroll across as part of Quebec City’s 1908 tercentenary celebrations.

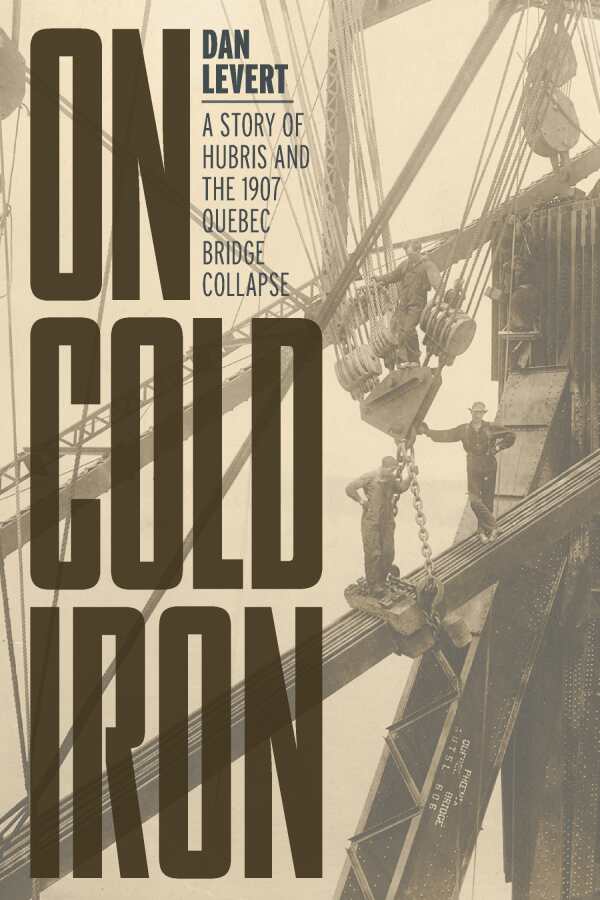

As a civil engineer, Levert gives a knowledgeable and detailed account of what the many personalities in the bridge design and construction did well and did poorly. The Quebec Bridge People, from First Nations riveting gangs to underqualified, overconfident engineers, are helpfully summarized for easy reference in short biographies in the rear matter. There are also numerous photographs of the bridge under construction and after its destruction, as well as a technical glossary and illustrations, that enhance the text.

For the most part, Levert’s chronology is cool and journalistic, though he inserts frosty condemnation for instances where critical mistakes or assumptions were made. He has no tolerance for inadequate testing of designs, sloppy management, or for the government’s complete abdication of their oversight role. His most passionate writing comes in the later chapters, when he reviews the Royal Commission of Inquiry’s investigations and findings. Here, Levert highlights some of the most dramatic and poignant survivor stories and hones in on numerous unanswered questions and avenues of investigation.

On Cold Iron is an outstanding historical and technical study of an avoidable human tragedy. Levert is generous with his professional knowledge and well describes the arcana of bridge design and construction for a general audience. This book is a great addition to the literature of Canadian history and popular science, and a cautionary tale about the importance of rigorous professional practices and oversight in matters of public safety.

Reviewed by

Rachel Jagareski

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.