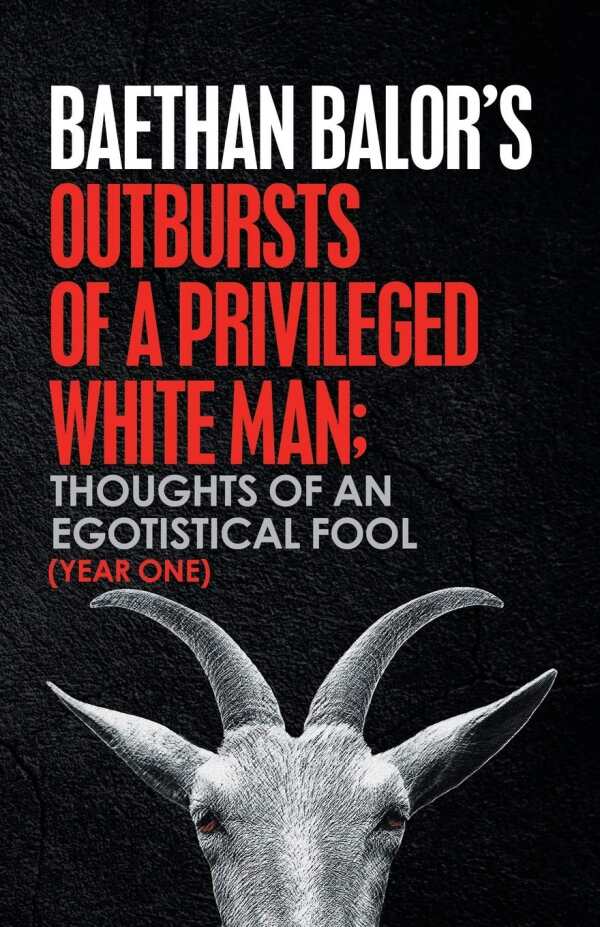

Outbursts of a Privileged White Man

Thoughts of an Egotistical Fool

Balor’s journal is an incisive glimpse of the current state of American psychoses.

More than just a year-long journal, Baethan Balor’s Outbursts of a Privileged White Man explores big ideas in the cloistered world of his suburban home.

Balor begins his journal on November 20, his twenty-fifth birthday, proclaiming “I identify as an ascetic, a fool, a sociopath, a rogue, a romantic, and a charlatan; but most of all, a fool.” He lives with his father and works as a janitor at a grocery store—a job he later quits, then resumes. He works out, fasts, eats, hangs out with acquaintances, writes, and reads the work of famous philosophers. He avoids close friendships and recently ended a long relationship.

The journal shows Balor growing sadder as he finds himself with more leisure time. He hears voices in his house and wonders if he’s schizophrenic. The book works its way around to an ending that is much like its beginning.

The book is predicated on what it is not: It is not the novel Balor wants to write; it is not a finished product. It leaves in its crossed-out lines. Also uncensored are the mostly medieval-set vignettes scattered throughout, dripping with morbid originality. There is no setting—only flags bearing symbols of successive holidays, waving in front of a neighbor’s house. Balor does not explain his terminated relationship with his girlfriend or his absent mother. There is no answer to the question of whether he is schizophrenic, and Balor seeks no solution to his sadness or madness.

This book, then, is not an edifying treatise inspired by other privileged white male writers. Rather, it reflects the vapidity which that same status offers Balor. What remains is a well-paired antecedent to a devoid predicate: a raw subject, whose unfettered musings, active contradictions, and solipsistic renderings of himself are an incisive glimpse of the current state of American psychosis.

The book’s lack sets its tone. In being so removed from anything expected, it is frustrating and disturbing. Its characters lend themselves to critique, whether they are black-clad and book-toting, drug-using and drunk, sex-crazed or devout Christians. They are full of vices with a dash of decency. Their conversations, while curt, are recorded verbatim. Balor’s short interactions with his father, in particular, are equal parts horrid, comic, and tenderhearted. What goes unsaid speaks volumes to his deprivation.

Perception is a primary preoccupation of the narrative. Balor imagines why anyone would want to read his work. Indeed, his candid point of view demands a retort. Indifference is not allowed in the world of this book. The result is a provocation to take part in the interplay of Balor’s thoughts.

Balor thinks of calling his book “What Not to Do with One’s Life.” Being trapped in the mind of a Privileged White Man turns out to be the perfect opportunity to take stock of one’s own psyche.

Reviewed by

Mari Carlson

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.