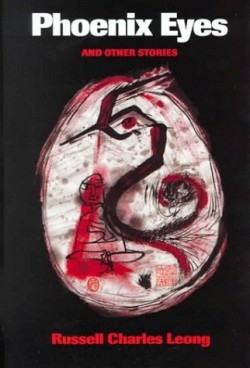

Phoenix Eyes

and Other Stories

Exploding traditional stereotypes, the Chinese Americans in Leong’s collection of short stories rarely see the inside of a university, let alone become computer geniuses.

In the fourteen stories contained in Phoenix Eyes, Leong explores the underside of the so-called “immigrant experience.” The Chinese-American men do not work in restaurants before moving to the suburbs; rather, they make their way in America by becoming sex workers or turning to alcoholism. Their lives are torn apart by war, AIDS, and the marginalization that comes from being a stranger in a new land.

The title piece, “Phoenix Eyes,” describes the life of Terence, a bisexual middle-aged Chinese man who, after graduating from Washington State University, goes to Asia to make his name as a stage designer. Initially intending to return to the United States with laurels and fame, Terence instead falls into the international flesh trade, using his body and those of disaffected business travelers to support himself. A shadow falls across his life when his mentor and lover, P., becomes sick and ultimately dies from AIDS. As Terence returns to the United States, Leong combines the Buddhist belief in rebirth and the phoenix image to convey redemption and the continuing cycle of life.

Similar feelings of dislocation and thwarted desire thread throughout the rest of the stories. They are divided into three parts, Leaving, Samsara, and Paradise, which parallels the sense of movement and struggle that Leong’s characters face. In “Eclipse,” Leong showcases his range of writing techniques by using a drama format to illustrate the limitations of a closeted homosexual, yet sexually curious Japanese-American professor. Another fine story, “A Yin and Her Man,” describes the end of a relationship and what it means to be the rejected party. Leong manages an impressive range of voices throughout the book, bringing the reader in close contact with a panoply of well-drawn characters.

As the editor of Amerasia Journal, Leong is well-steeped in the rhetoric of current cultural criticism on what it means to be Asian-American. While his sometimes harsh naturalism and masculine aesthetic draws the comparison to predecessors such as Frank Chin, the sophistication of his stories suggests a new generation of dialogue about Asian-American identity. (July

Reviewed by

Johanna Massé

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.