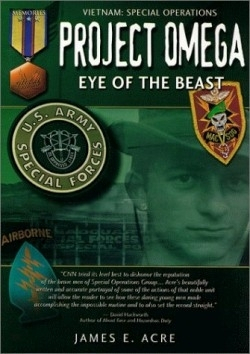

Project Omega

Eye of the Beast Vietnam-Special Operations

David Hackworth, America’s most decorated living soldier and author of About Face and Hazardous Duty, calls James Acre in the introduction “an idealistic teenager who quit college and joined the Army during a very bad war.” Acre spent 1969-70 as a member of the Military Assistance Command Vietnam—Studies and Observations Group (a less menacing description than Special Operations Group). This highly specialized, clandestine branch of the military would not allow its members to keep diaries or mention their work in letters home, under penalty of ten years in prison and a $10,000 fine. If a member died, the army would deny any knowledge or responsibility.

Acre presents a soldier’s tale of harrowing reconnaissance missions in Cambodian jungles, along with stories of the fine and not so fine young soldiers—several whom were killed—he served with and became, if not their brother, a friend unlike one he could become in civilian life because their survival depended on their camaraderie. In addition are many humorous, raunchy anecdotes about trysts with the ever-present town prostitutes and pot smoking, which was a common and cheap way to relieve the stress of combat assignments.

Missions took as long as four sleepless nights and days in jungles so thick that at night Acre could not identify friends or foes only a few inches away. He admits mistakes and doubts as he matures from a raw recruit into a Green Beret sergeant, well respected by officers and enlistees. Acre’s specific reconnaissance role was radio operator, communicating and directing troops and helicopter support. Aside from North Vietnam regulars, he battled ferret-size rats, leaches, monsoons, dysentery and an array of exotic venereal diseases which he caught four or five times.

Since Acre was not allowed to keep a diary, the events are related sometime after they occurred; this memoir falls into the category of creative non-fiction. The book would have been improved upon by a narrative of Acre’s life before and after his service. Yet the author sustains the reader’s interest throughout, and photographs of the men he served with and a glossary of military terms and slang enhance the book. Acre earns the reader’s respect for offering an honest self-portrayal of a soldier who came to doubt the motives for the war but who at a very young age honorably served his country.

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.