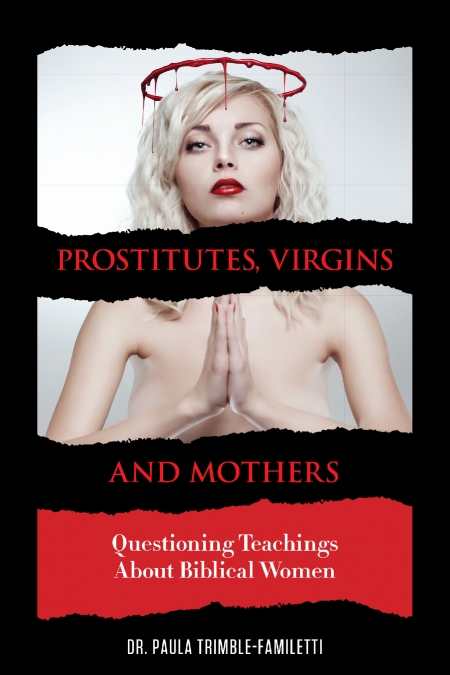

Prostitutes, Virgins, and Mothers

Questioning Teachings about Biblical Women

- 2014 INDIES Finalist

- Finalist, Religion (Adult Nonfiction)

From a feminist theologian comes a fascinating and passionate introduction to women in, or, more accurately, women’s exclusion from, the Bible.

A self-described cradle-Christian, Paula Trimble-Familetti, a graduate of Liberty University and a feminist theologian, began to notice, through practice and study, how religion was deeply and needlessly gendered. This project is part of an attempt to correct that injustice and encourage a more rounded exploration of Christian faith: “if women’s voices and experiences are silenced,” she says, “half of God’s self-revelation, half of the human experience of God, is lost.” By tracing women connected specifically to Jesus, her pages seek to illuminate women who were both essential to Christianity’s emergence and were intentionally silenced as it grew.

Trimble-Familetti calls portions of her work midrashic; these hope to give voice to some of the 111 women she says are mentioned by name in the Hebrew Bible (as opposed to her estimate of roughly 1,500 named men), as well as New Testament female fixtures. She retells the stories of Sarah, Bathsheba, and Rebekah, amongst others, altering little from their biblical biographies but allowing those biographies to come through their voices. Such sections recall other feminist retellings, like Anita Diamant’s The Red Tent, if they take fewer liberties.

Simultaneously, Trimble-Familetti provides a historical account of what women’s lives were like in ancient Israel, connecting their hardships with the decision of the biblical writers to mention women only where their stories illuminated those of men. She points out that even women given credit in New Testament texts were injured by later, often baseless, interpretations, as well as by tendentious translations (as with diakonos, translated as “deacon” for men vs. “servant” for women). Magdalene is rescued from the fallacy of prostitution and is highlighted as a beloved disciple; prophets and church mothers like Prisca and Susanna are reintroduced; Mary is afforded the sympathy often denied to her.

The more just and accurate picture, she argues, should be one of an early church utterly reliant on women’s contributions, one which followed the teachings of a man continually concerned with care for the marginalized, women chief amongst them.

Prostitutes, Virgins, and Mothers travels familiar ground in feminist biblical studies, but its willingness to discuss women’s absence in the text while simultaneously engaging biblical stories as originally presented may offer inroads for more traditional readers. At the same time, the passion and candor with which she speaks of post-canonization patriarchal silencing of biblical women will charge more seasoned feminist readers. That her work covers such diverse ground makes the book a unique and worthwhile read, and those eager to investigate the real place of women in religion would be well directed toward this text.

Reviewed by

Michelle Anne Schingler

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.