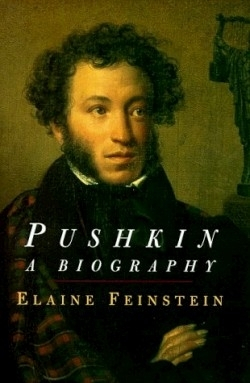

Pushkin

A Biography

He was descended from the blackamoor of Peter the Great, loved the bar and bordello, fought duels and debts, had “a proper monkey’s face” and was five feet tall. Yet this same imp married a girl of renowned beauty and wrote luminous poetical lines. He is Russia’s national poet and his stature is that of Shakespeare’s.

Pushkin’s name is pervasive in Russia. Children of pre-school age learn about him first as a ubiquitous ghost: his name is always in the air. They start studying and memorizing his fairy tales in first grade and continue with his lyrics, ballads, narrative poems, folk tales, dramatic writings and prose throughout high school. Pushkin’s style is clear and simple, says biographer Feinstein, and his imaginative power has Byron’s facility, Keats’ sensuousness and Chaucer’s bawdy wit. Pushkin’s creative power was similar to Mozart’s; both had God’s light of genius shining through them and both were scamps.

Alexander Sergeevich Pushkin (pronounced Poosh-kin) was born in Moscow May 26, 1799. His father was descended from ancient Russian nobility and appreciated Russian and French literature. Pushkin’s mother was the grand daughter of an African slave who became Peter the Great’s godson. Pushkin’s nanny told him folk tales and local gossip thereby interesting him in stories. He also learned more from visits to his father’s study than he did from tutors. After dinner, the eight-year-old would listen to his father’s friends, the literati of the day, recite poetry, bawdy or otherwise, listen to tales from abroad and hear morsels of gossip with just the right flavoring of myth and mirth.

From 1811 to 1817 Pushkin attended the Lyceum at Tsarskoe Selo, a boarding school under the aegis of the Tsar. He became known for his witty epigrams and exquisite elegies—and for participating in the same lascivious enjoyments as the off duty soldiers in town. After graduation he accepted a minor post in the Foreign Office. At the same time he had written poems of a subversive nature, was scolded and sent to southern Russia to be watched.

As are most Russian poets, Pushkin is not well known in the West. This is not only because “It is the poetry that gets lost in the translation,” as Robert Frost said. Russian is the ultimately perfect language for poetry due to infinite possibilities of changing any word to create a perfect rhyme, an atmospheric metamorphosis of a sentence or an elicit chain of allusions. An example is Evgeny Onegin, Pushkin’s masterpiece of 400 fourteen-line stanzas in iambic pentameter, which is a story of unrequited love yet also an “encyclopedia of Russian life.”

There have been many translations of Eugeny Onegin, and sometimes the translators fight like schoolboys about how it is to be done. Vladimir Nabokov said that the figure of speech is the essence of a poet’s genius and that Walter Arndt’s translation used crippled clichés and mongrel idioms. Douglas Hofstadter, a critic of translation, said Nabokov’s literal translation without rhyme and meter was “catastrophic.”

An example of two different translations of Evgeny Onegin, Chapter Four, Verse XXII: “But whom to love? To trust and treasure?/ Who won’t betray us in the end? (Feinstein); “Of whom shall we bestow affection,/ And whom shall we confide in, pray?/ In whom discover no defection.” (Deutsch).

When Pushkin returned to Moscow after his exile in Odessa and Mikhaylovskoe he was already a celebrated poet. At twenty-six he had written a drama, Boris Godunov, a tale in verse, Ruslan and Lyudmila and poems of a liberal nature. Later, he fell in love with the beautiful eighteen-year-old Natalya Goncharova and married her in 1831. In 1836 Baron Georges-Charles d’Anthes, a favorite of the Tsar’s court, began to pursue Natalya. The situation resulted in a duel; Pushkin’s life ended with a bullet in 1837.

Feinstein, a poet, novelist and a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature has written the first biography of Pushkin published in five years; it will coincide with the bicentennial of Pushkin’s birth. Feinstein includes new material on Pushkin’s last years before his death. Her biography is written without the academician’s jargon providing interesting details that general readers of biographies enjoy. With skill she intersperses family history, political background and summaries of his works to keep the reader’s interest.

Pushkin said that writing poetry gave him the most constant pleasure in his life; Feinstein’s style evidences her pleasure in the writing of Pushkin. The reader will have pleasure in the reading of it.

Reviewed by

Julia Bushkova

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.