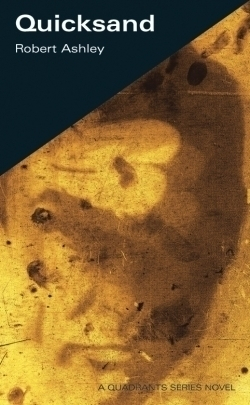

Quicksand

The Critic’s Handbook to Pontificating About Everything offers no guidance on how to assess the quality of an opera libretto that’s written in the form of a mystery novel—which is precisely what Quicksand announces itself to be. So one is left to answer that most basic of literary questions: Does the work say something well? Here, the answer is “yes”—but with certain provisos.

Now eighty-one years old, Robert Ashley has had a distinguished career in creating experimental forms of opera, examples of which include Perfect Lives, Atalanta (Acts of God), Now Eleanor’s Idea, and Foreign Experiences. Ashley says in his preface that he wrote Quicksand partly in response to critics who contend that his operas have no plots. To address that charge, he employs literary techniques in this book more common to crime novels. “I am devoted to ‘mystery’ stories,” he explains. “Some of the best writers today are writing in this form.”

Quicksand is narrated in first person by its protagonist, an elderly American composer of operas who doubles as a spy for what appears to be the CIA. Nearing retirement, he reluctantly accepts another assignment when he joins the members of his wife’s yoga class for a tour of “some countries in South East Asia.” The shoot-‘em-up action—and there’s plenty of it, starting with the first scene—takes place in an unnamed country ruled by a dictator. The narrator’s job is to facilitate the dictator’s overthrow by working with a shadowy group of rebels who seem more picturesque than political.

No one has a name in this story, not even the narrator. But he does assign a few of the main characters fanciful monikers. One of his contacts is “Mr. B,” another “Soapy.” The young rebel girl he almost falls in love with is “Pooh.” (Besides the impending rebellion, the narrator and Pooh are bound together by their passion for such pop culture icons as mystery writers Elmore Leonard and Michael Connelly and country music stars George Jones and Patsy Cline.)The action takes place with comic-book speed and directness, and the only head the reader gets inside of is the narrator’s. All the other characters’ motivations are seen through his eyes and explained in his voice.

The narrator’s lack of specificity about his major characters and events might sound confusing or coy, but it actually serves to endow the story with a timeless, fairytale quality. Taken overall, Quicksand is less a mystery novel than a dream-like tale of a weary knight’s last crusade. And that’s the stuff of opera.

Reviewed by

Edward Morris

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.