Rending the Garment

Schneberg’s poetry is both a quiet reflection on the brevity of life and a celebration of how full it is.

“In Jewish ritual clothes are torn in mourning.” This sentence precedes Willa Schneberg’s title poem in Rending the Garment and creates a beautiful image of tradition, grief, and purpose. Willa’s book is more than poetry; it is a collection of memories, letters, truths, and fiction which span decades of life within a family. From tender adolescence through the indignities of advanced age, Schneberg plays with perspective to broaden the portrait of her family and delivers a robust and bittersweet narrative.

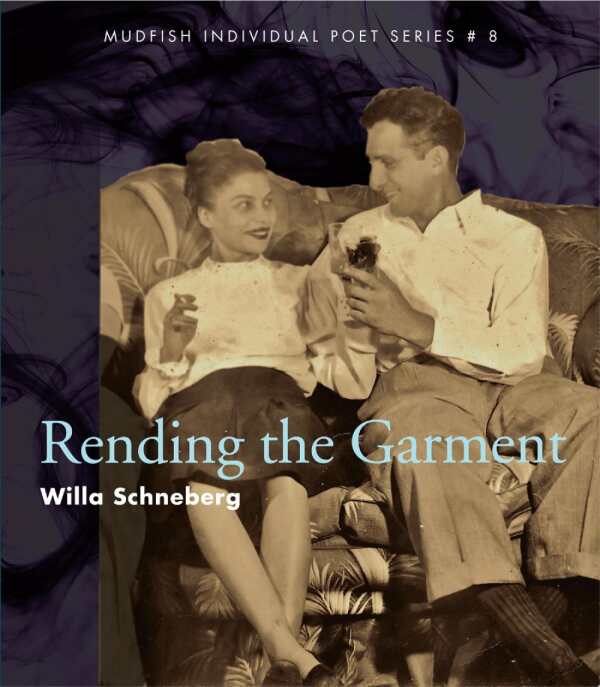

Section one, “Ben, Esther, & Willa,” explores the family of Schneberg’s childhood. These pieces look back at the traditions of old neighborhoods, reconciling them with “the land of the icebox and washboard.” Schneberg has romantic ideas about her mother in her dark red lipstick who “drank New York, but never more than two Jack Daniels and Coke.” On the book’s cover is a snapshot of Esther and Ben. Both are invincibly smiling. Poems and letters in this section also give flesh and blood to Ben, who tries and fails at being a teacher and overcomes an intense fear of tunnels. In a stunning poem, “Ben Schneberg Writes To Emily Dickinson,” he empathizes with the famously fearful Emily Dickinson saying, “all I ask is that you open your gate and extend your hand.” Each piece of writing connects this family with the world outside of itself—whether social, political, or interpersonal. The section closes with the death of Ben and the unpolished elegy left by Esther, thanking him for small things.

Section two, “Esther & Willa,” focuses on a daughter caring for her aging mother. Refreshingly, so many of the pieces written from Esther’s perspective are wry and alive, keeping this chapter from weighing itself down. The loss of Esther’s voice due to a laryngectomy becomes central to this section, which is gruesome and pitiful but also empowering and sympathetic. There is no veil of discretion over describing a life without the ability to eat through your mouth and the challenges this presents, but the thread of mother and daughter is still strong between these two women who reverse their roles. It is a raw and illuminating way to walk with someone during the last months of their life.

Finally, Schneberg closes with the brief section three, “Willa,” which feels a lot like the author walking through the rooms of an empty house once occupied by her family. The sense of irretrievable loss and the inevitability of Schneberg’s own aging and death are not overly melancholy.

Rich with heritage and history, Willa Schneberg’s writing is intensely personal but delivered with connection to the changing context of American life through each decade.

Reviewed by

Sara Budzik

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.