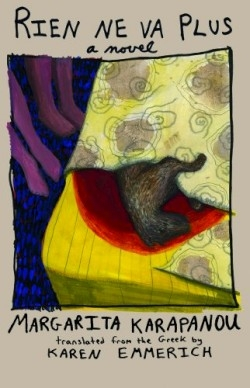

Rien ne va plus

Rien Ne Va Plus tricks its reader by a rapid mid-point shift from realism to metafiction-but only after the reader has fallen in love with Karapanou’s writing, and her inimitable main character.

No sooner does the reader sympathize fully with the maligned narrator, whose control-freak husband Alkiviadis invites a fifteen-year-old boy into their bedroom on their wedding night as a way of introducing her to his gay proclivities, than does Karapanou suggest that Alkis’s sadism is a possible fiction and that his only error was to be an ordinary man (“youÂ…didn’t have the imagination, madness, or balls to become an alchemist of life like I was”). Karapanou renders her plot believable by making her protean narrator a novelist, whose prior framing of Alkis as demonic was a way for the narrator to keep her inner freedom. According to the protagonist’s own “confession” to him in the latter half of the novel, “You were really the one who lied. You wanted everything to remain untouched, paradise to be paradise, and me an angelÂ…you never understoodÂ…that through my lies I was giving you a unique gift: the truth.”

An ars poetica for the craft of fiction, yes, but also an as-yet-undefined genre of writing, in which metafiction, fantasy (while living in Connecticut she spends most days with her neighbor Mr. Brenneman, watching Love Boat, while the state floods), Dostoevskian drama (she wins a large sum gambling, after the fateful words “Rien ne va plus”-all bets are off-are spoken), horror (a graphic third-trimester abortion), and the most radical of subjectivities by a woman protagonist meld together only to disappear. The scene that drives home the need for anonymity takes place when the narrator writes her ostensible name, Louise, in the steam of a bathroom mirror, then erases it, to better see her face.

Set primarily in Glyfada, Greece, the roiling European excesses of this book (anchored by the opera La Traviata and Giorgione’s painting La Tempesta) please and astound. Larger-than-life characters such as Vanessa and Aunt Louise, the panoply of domestic animals, and an aphoristic section composed of existential meditations all contribute to this fiction of fictions, whose explorations of the nature of love, sadomasochism, and self-discovery invoke the work of Kate Chopin, Mary Gaitskill, and Kate Braverman’s Lithium for Medea, in turns. “The end has arrived,” says the narrator, resting between transformations. “But not even that can release me. Because there is no End. Amen.” (October) Virginia Konchan

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.