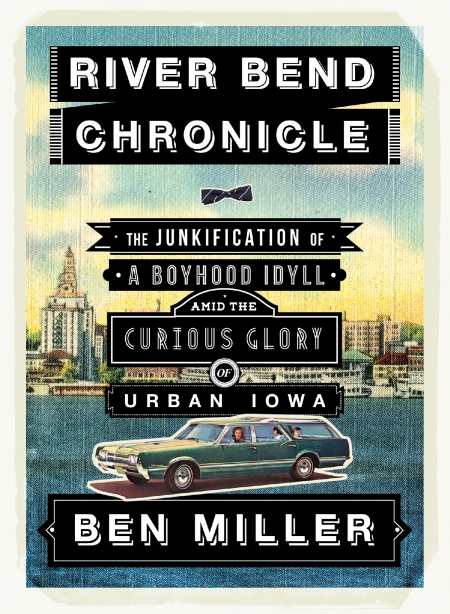

River Bend Chronicle

The Junkification of a Boyhood Idyll and the Curious Glory of Urban Iowa

Ben Miller’s River Bend Chronicle contains 472 pages of circuitous, dense, and nonchronological essays harboring geodes of insight carried along by a cast of characters ranging from riotous to pitiful. Framing this autobiographical narrative and providing the self-reflection the essays sometimes lack, the epilogue and prologue reveal secrets that will expand the unsuspecting reader’s capacity for empathy.

The junkification of Miller’s Davenport, Iowa, is a common tale in America: “Fewer and fewer citizens shopped downtown now that Northpark Mall had opened on the outskirts, joining popular discount barns Kmart and Target.” He grounds his memoir on a particular river bend “alongside the wide Mississippi, which had become a huge freshwater jigsaw puzzle, as it did each December, its gray-blue ice slabs stacked like flapjacks or pushed into teepee formations by the frigid cocoa current. Sewage plant. Hostess Twinkie factory. Robin Hood Flour Plant. From a distance the emaciated skyline of downtown Davenport promised nothing sweet.”

Sweetness is spare in Miller’s recounting of life with five siblings and two law-degree wielding, but unsuccessful, parents; his father was largely apathetic and depressed and his mother manic and unfocused. Loneliness and isolation within a household of eight seems unlikely, but Miller reveals sexual abuse by his mother beginning “when I was eleven, and she had put infant Nathan down for the night.” He makes the choice at fourteen to begin refusing her advances and becomes anorexic—his way to “eliminate the fat boy she’s been so close to for so long.”

That same year, Miller also joined the Writers’ Studio: “For all the group could not do for me, they did a child of chaos a sweet favor by just being there, week after week.” It was in the Studio group that Miller worked out “that tic of mine to respond to family debacles not by patently rejecting them but by dragging them with me, out of their vile hole … [where they]—might be tempered, refined, and, instead of destroyed, lent the solidity of reality.”

Subjectivity can be a pitfall of any memoir, yet what Miller presents is a kind of forgiveness, brave, heroic, and largely uncharted by male writers: “There was more to my mother than her bedtime betrayals … I had let her get away with it … I had excused her a thousand times in the name of pity or even respect.” Because Miller assumes a complicit role in his molestation, he lends empathy and strength to a story that could otherwise be just one of victimhood.

Miller is a widely published essayist—with pieces in The Kenyon Review, Antioch Review and AGNI, among others. His essays have been noted or reprinted six times in Best American Essays. He was also the recipient of a creative writing fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts.

Reviewed by

Kai White

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.