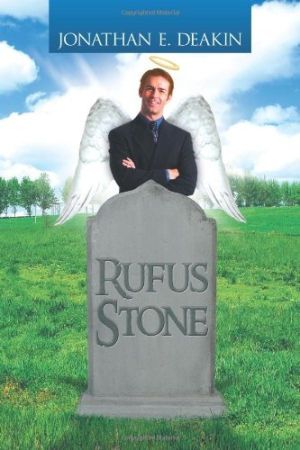

Rufus Stone

Kent, England-based Jonathan E. Deakin’s new work features an angel whose curiosity about human experience prompts him to choose a British couple as his parents and to become the titular Rufus Stone. From this promising idea, minor adventures arise, including visiting an aging relative, reporting a robbery, competing in a race, and befriending a fallen angel, James, whose longing to reunite with his father informs the latter part of the book. Situations resolve with minimal consequences, and the main character, Rufus, possesses few flaws—an understandable choice for an angel, but less compelling as a fictional protagonist readers can empathize with.

Heaven in the novel is a curiously innocent place. Interceding on behalf of a fallen angel is possible, and “when you are immortal, the concept of death—or losing someone you love, forever, is impossible to grasp.” This suggests that angels have not been impacted by the story of the crucifixion/resurrection and its inherent darkness. Instead of appearing as figures with impressive power that engage in an inspiring, metaphysical battle, angels are mostly benign helpers who orchestrate events and visit those nearing death. Fallen angels are impish and vulnerable to impulse rather than evil, though the Devil, as represented here, maintains an appropriate level of deceit.

About writing fiction for children, Madeline L’Engle, author of A Wrinkle in Time and a noted Christian, once wrote, “The techniques of fiction are the techniques of fiction. They hold as true for Beatrix Potter as they do for Fyodor Dostoyevsky.” She also believed that a child “is willing to sail into uncharted waters,” implying that writers should not dilute their approach, and should trust younger readers to understand more than they are given credit for.

Such views would strengthen Deakin’s book, as the author leaves little room for readers to draw inferences. He offers emotional cues through exclamatory remarks, and frequently employs an italicized, occasionally boldface authorial voice to comment on forthcoming events and to explain scenes, such as, “Rufus had just been given a lesson in humility by James,” “James had learned a very painful lesson about regret,” and (about Rufus) “He was being tempted!” Such interjections remove suspense.

Though Rufus Stone raises worthy questions of friendship, family, redemption, loyalty, and faith, without thorough characterizations, an allegorical framework (as with C.S. Lewis’s Narnia), or plot elements that could freshen the story and its timeless wisdom, the book remains an earnest morality tale.

Reviewed by

Karen Rigby

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.