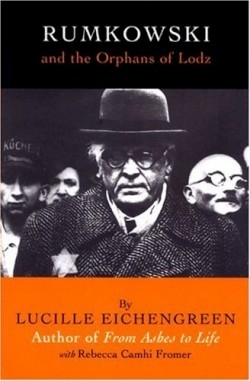

Rumkowski and the Orphans of Lodz

“If the idolators say: ‘Hand over one of you and we will kill him; or we will kill all of you.’ Then let all be killed but do not hand over even one soul of Israel.” Chaim Rumkowski, the Elder of the Jewish Council in the horrific Lodz ghetto in Poland, ignored the teachings of Rambam (Maimonides), ignored his faith to become a willing lapdog to the brutal Nazi regime.

“Collaborator.” The term reeks of evil when placed in the context of World War II and the atrocities committed against innocent people. Rumkowski, collaborator. Eichengreen, known as Cecelia Landau during her stay in Lodz, survived one day at a time as her mother died quietly of malnutrition and hopelessness, and her little sister fell victim to the roundup of all children under ten and elderly over sixty-five. She was eleven.

As Cecelia, barely eighteen, struggled to work so she would be eligible for the watery cup of soup at lunch each day, she wondered about the man whose name appeared on the bulletins ordering everyone around: Rumkowski. She knew he was well-fed, expensively clothed with boots just like the Nazis wore and omnipotent within the ghetto. Supposedly, he had the best

interests of the prisoners in mind as he requested extra food to stretch the meager twenty-eight grams of bread allotted daily per person with slivers of potato and occasionally meat, horsemeat. All he asked in return was blind devotion as he systematically stripped his people of dignity, heart and soul.

But Cecelia questioned. Quietly, so she wouldn’t be punished, she asked questions of Shlomo Berkowicz, an elderly man who ran a small streetcart filled with the remains of his once large store. He knew a man, before the war, named Sergei, who took the accusations of three children who lived in the orphanage at Helenowek seriously. Luba, Julek and Bronia told similar stories of being sexually abused by the director of the orphanage: Rumkowski.

During the four years Cecelia spent in the ghetto, she met Little Bronia, a girl suffering from dwarfism, who confirmed Berkowicz’s story and was horrified by the fact that she now worked for Rumkowski as a messenger to survive. Luba, when Cecelia met her, used her past connection with Rumkowski to obtain extra food for her lover. Both girls silently allowed Rumkowski to abuse them to survive. Even with the stories she collected, Cecelia never expected to come to his attention herself or to fall victim

to his sexual predations. In a war where survival was an everyday occurrence, she found his attentions “insufferable.”

Through blind luck, Cecelia survived the liquidation of the Lodz ghetto, hearing and hoping that Rumkowski died with the final trainload. She met Julek, who had joined a partisan group during the war to avoid incarceration in the ghetto and eventually found her way to America. Her first two weeks were unbearable as people treated her like a contaminated substance, but she lived, married and found a measure of joy. In 1975, Lucille met a man named Sergei, the same man who investigated Rumkowski before the war.

Was Rumkowski a misunderstood man trying his best to save his people, or was he only interested in saving his own skin? With the publication of Eichengreen’s biography, there can be no doubt that a devil walked among the prisoners in Lodz.

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.