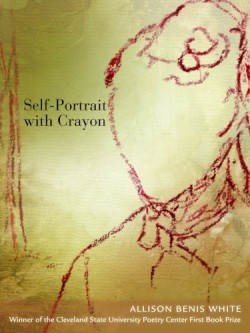

Self-Portrait with Crayon

- 2009 INDIES Finalist

- Finalist, Poetry (Adult Nonfiction)

The poems of Self-Portrait with Crayon are haunted. There are no ghosts or goblins lurking, but rather an absent mother and Edgar Degas.

The two apparitions seem unconnected until Allison Benis White skillfully commingles them. The first poem of this collection, “From Degas’ Sketchbook,” finds the speaker hiding in a closet, imagining her mother: “The shoulders are the span of the hanger and the mind is the hook which suspends the entire dress.” It is as if the outline of the clothes allows her to color her mother into the picture and into the book. Degas serves as a means to contemplate abandonment. All of White’s poems share titles with the artist’s works, including the famous “Dancers in Blue” and “After the Bath.”

These ekphrastic poems often begin with a feature of the original painting and expand to include the speaker’s world. Her first insights are childish—not infantile, but open-minded in the manner particular to children. There is a willingness to accept the unexplainable. That open-mindedness eventually leads to otherworldly insights; that is, they feel true, but how could anyone know? In “Ballet of Robert the Devil,” White suggests, “Even heaven, like dolls, cannot love without imagination.”

It is not only the content of White’s poetry that is haunted, but also the approach. The thirty-five prose poems are fragmentary, only filling in some of the details. Even the definitions of words are slippery, often losing their established meanings to take on White’s. Although a few of the details from the speaker’s childhood seem sentimental, they create a believable character. As the title suggests, Self-Portrait with Crayon draws a portrait and introduces a promising young poet. While individual poems have appeared in well-known journals, this is White’s full-length debut. It won the Cleveland State University Poetry Center First Book Prize.

Using paintings, sculptures, and drawings of Degas lends the poems imagination to complement the melancholy at the collection’s core. For example, “La Savoisienne” allows the speaker to project herself onto the unnamed peasant that Degas rendered. White proposes what might happen to the girl beyond the painting. In this way, the poet gives life to a figure as she gave life to a hanger. Both peasant and poet believe “There are at least seven kinds of loneliness.” But is it White who breaks the long silence and gives voice to the lonely and the absent—herself, her mother, and Edgar Degas.

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.