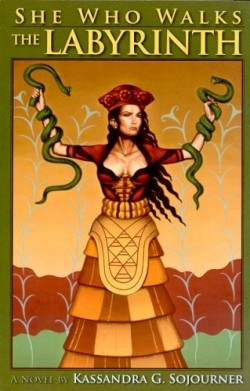

She Who Walks the Labyrinth

To the unhappy inevitability of death and taxes should be added one more grim reality: the misery of the teen years. Even in a society that is as woman-supportive as Minoan Crete, being a teenage girl just plain hurts.

The author is an ordained priestess in the Re-formed Congregation of the Goddess, International. This is her first novel, and it chronicles the entry into adolescence of two young girls, Ansel and Geneera, in Kriti Crete) around 1,500 BCE. The story begins when both girls are about fifteen years old and living in Knossos, Kriti’s most cosmopolitan city.

Ansel is bright and highly sensitive, but uncomfortable meeting strangers and painfully insecure about her looks. After surviving an earthquake several months earlier, she has been experiencing inexplicable visions and nightmares, making her fear that her mind is coming unhinged. Her best friend, Geneera, hopes to realize a lifelong dream of becoming a bull dancer. When she is invited to join the troupe, she finds the way resolutely blocked by her mother, who has already lost Geneera’s brother to the bull dancer company when he died on the horns of one of the animals. The author deftly intertwines the escapades of the girls with other plot lines and much larger issues as the story develops.

Sojourner’s prose is imaginative in recreating ancient Crete, since not much is known about the book’s actual historical period. Based on the scant surviving art of the country, some scholars theorize that Minoan Society was non-militaristic and non-violent, and worshipped a Goddess instead of a male deity. The author draws directly on these theories in constructing a picture of the daily routine of the citizens. Though the book can be read as a coming-of-age story, its bigger canvass gives the narrative a wider appeal as an exploration of how people deal with change. Not the rhythms of change, but its unpredictable starts, stops, and switchbacks that can so easily disorient a person or even an entire culture.

The biggest change for peace-loving Kriti is how to react if attacked by one of their increasingly bellicose neighbors. If they fight, they betray their deepest convictions. If they don’t, they could perish. “To me the choice seems between to die a thing beloved or to survive but become what is hated,” Ansel rails. “I would rather die than take up arms … to train people for the military, it eats at the very soul of a nation.”

Certainly these words could apply to many societies and times. The ending of the book seems slightly unresolved, like a lead-in to a sequel, but for the most part the novel is engaging and smoothly written. Its strength lies in the author’s ability to create complex characters whose difficulties and emotions are very much like the reader’s own, even though these girls lived thirty-five centuries ago.

Reviewed by

Leah Samul

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.