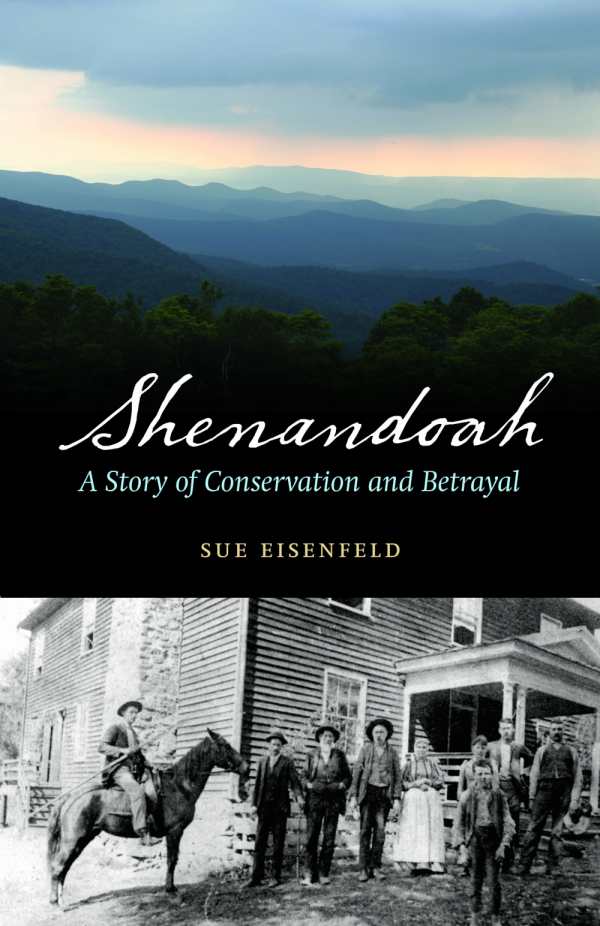

Shenandoah

A Story of Conservation and Betrayal

Rich portraits of the people who were displaced when the Shenandoah National Park was created are both heartrending and ironic.

Each year, a million tourists traverse the “lizard-shaped” Shenandoah National Park by car on the Skyline Drive atop the peaks of the Blue Ridge Mountains. Many of these visitors disembark to explore its many trails, and a smaller coterie of off-trail hikers descend into the backwoods. Sue Eisenfeld is one of the latter, though her passion for wilderness has gradually been eclipsed by a curiosity about the cemetery markers, stone chimneys, and other testaments to the people who lived here before the park opened in 1935. She chronicles the stories she uncovered in Shenandoah: A Story of Conservation and Betrayal.

Eisenfeld is not ambivalent about the great public benefit the park provides. She firmly advocates that this “de-peopled and re-wilded” national park should have been built, but argues for greater recognition for the sacrificed 450 families that were clumsily uprooted from this spectacularly beautiful place. She overlays prose pictures of present-day hikes and interviews with displaced Shenandoah descendants with historical research about some of the original residents and power brokers.

Eisenfeld acknowledges that Shenandoah and other national parks are “pockets of refuge in a country that is full of painful views” and gives a much fuller picture of how this relatively young park was created at great cost to the families who had lived there. She documents how the Shenandoah residents were disparaged in a shameful 1930s propaganda campaign as being uncivilized hillbillies and expands on official national park literature about how families were treated once they received their official eviction notice. Some were resettled in nearby communities, some were forcibly evicted, and some were allowed to live out their lives at the park.

There is not enough discussion of the irony that the Shenandoah residents had themselves displaced generations of Native Americans from these same lands, or the lack of photographs of Shenandoah settlers. These are minor issues, however, in an otherwise richly textured look at the human drama of creating one of the jewels of the national park system.

Reviewed by

Rachel Jagareski

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.