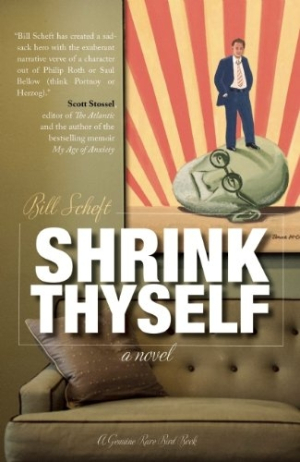

Shrink Thyself

This full-on satire gives voice to wry observations about baby boomer life, nicely linking theme to character.

In Shrink Thyself, a character study masquerading as black humor, author Bill Scheft tosses enough troubles in Charlie Traub’s path to send a lesser man running home to mother.

Actually, that’s what Charlie does, except his mother is dead, leaving him obligated to make $7,500-a-month payments for her Windgate Point apartment. The will? Rewritten, but the sole beneficiary, his sister, won’t speak to him. Then there’s his ex-shrink, who showed up uninvited at the funeral and ended up committed to a mental institution. Save girlfriends and ex-wife for later. And so it goes for Charlie, a decent sort, trying hard to please, until he realizes that as “Your issues get smaller, your conscience gets bigger.” Maybe it is possible to shrink thyself.

Charlie’s world is the D.C.–New York City–Boston power corridor, a setting deftly brought to the page. He is a freelance television producer whose Beltway Today became must-see TV during the Clinton impeachment carnival. The star, panelist-professor Bonnie Dressler (think Ann Coulter as a red-headed liberal) plays a part later in the narrative. Charlie develops into a worthy protagonist. Something of a hapless fellow, he soon latches onto the idea life is an “imperfect pursuit,” but that realization only comes after misadventures with his ex-wife, his mother, Dressler, Dressler’s sister, blind dates, and his shrink going bonkers. That shrink has mommy-issues enough for a Freud field day.

Another fun character is retired professor Sy Siegel, a Marxist conspiracy nut with no filter between thought and speech. Siegel happened to be in flagrante delicto with Charlie’s mother’s when she died.

While complex, Scheft’s plot is easily parsed, moved along with natural dialogue and breezy writing, the sort of rollicking good-times tale that is hard to put down. Contrary to much comedic writing, Charlie is entirely believable as a man immersed in his own affairs or reluctantly drawn into the worlds of the other characters.

Sticklers may quibble over the reason for Charlie’s divorce, but there is logic to it, and it fits the novel’s theme. Not much attention is paid to how Charlie funds his existential search for meaning. Those minor negatives are quickly drowned out as good guy Charlie gives voice to wry observations about baby boomer life, nicely linking theme to character.

There’s rank irony in the whimsical idea that a guy would drop psychotherapy in order to find himself, but adding an inept defrocked shrink to the fellow’s journey rigs the boat for full-on satire. With his sly social observations of this postmillennial world, a talent for nurturing his emotionally hemmed-in protagonist, a soupçon of Jewish angst, and a gift for word play—“my rate would jump Shylockingly”—Scheft offers laugh-out-loud commentary on life, love, and loneliness.

Reviewed by

Gary Presley

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.