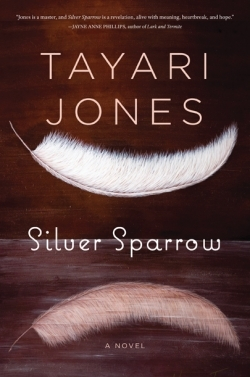

Silver Sparrow

“My father, James Witherspoon, is a bigamist.” Thus begins Tayari Jones’s latest novel, Silver Sparrow, a story that blossoms and winds its way around this one, life-making fact. Set in 1980’s Atlanta, the book peels open James’s life, or rather, his two lives—the one with his legitimate wife and daughter, Laverne and Chaurisse Witherspoon, and the one with his secret family, Gwendolyn and Dana Yarboro. Told from the points of view of both daughters, what unfolds in these pages has nothing to do with convention and everything to do with love, how it pushes and prods you to startling ends, and compels you to make choices you would never imagine.

Silver Sparrow is Jones’s third novel, and she writes with the adeptness and grace of one who is both gifted and highly skilled at her craft. Her narrators’ voices ring with authenticity, their openness frank and unflinching. The story holds not a wink of sentimentality or woe-is-me-ism, and it’s what allows Jones to more than pull off this tale of deception, secrets, and four women scorned. Dana states matter-of-factly that Laverne found James first and says, “My mother has always respected the other woman’s squatter’s rights.” Dana and Gwendolyn are not to be pitied, and yet, one can’t help but marvel at how they cope with such closeted ways.

Secrets—they seep into every speck and corner of the Yarboro’s lives, even down to their appearance. Dana says, “I looked so much like my mother that it seemed that James had willed even his genetic material to leave no traces.” At a young age, Dana learns her place in this complicated family: “You are the secret. [James had] said it with a smile, touching the tip of my nose with the pad of his finger.” Jones describes this moment with crystalline precision, makes the reader catch his breath and know that Dana will never unlearn this fundamental truth. Everything about her life’s path, from her summer job to where she wants to attend college, depends first on the direction Chaurisse chooses. Like any teenager, Dana has dreams, “but I lived in a world where you could never want what you wanted out in the open.”

Chaurisses’s existence is in direct contrast to Dana’s—she’s grown up believing that hers is the average life of a just-about-average girl. But as her part of the story progresses, she realizes how little she knows about her past and present, as well as that of her parents’, and how much she doesn’t even understand. She says, “It was like my mother was a newspaper that everyone could read except for me.” Her mounting awareness unfolds with grace, Jones’s touch feather-soft as she propels characters and reader alike toward the moment of discovery, when all the secret threads will be cut and unraveled.

Jones has a gift for imagery, for plunking the reader down in the chaotic, swirling center of teenage territory. Dana says, “By fifteen and a half, I had become obsessed with my own heart. I dreamt about it several nights a week. Sometimes it took the form of a pear, bruised and slimy in the bowl of my chest.” As she grows, Dana struggles to come to terms with love, for she has seen the weight it can hold over a person. Unlike Chaurisse, she understands too much, and as the knowledge begins to wear on her, disdain slips into her language: “I have thought back on this moment, as I have on many such moments of my life, and wondered why it is that I have been so careful with other people’s secrets.”

What lengths will one go to for family, for obligation? This novel calls that into question, and asks how someone can break free of the circumstances she has no part in forming. It makes one stop and look hard at friends and lovers, and particularly at oneself—what can be let go, or never given up? And what happens when what was once truth gets shattered? As Chaurisse says, “It’s funny how you think you can know a person,” but in the aftermath of catastrophe, love goes on—troublesome and complicated, and yet, alarmingly simple. Love that is unshakeable, even if one might wish it could be different.

Reviewed by

Jessica Henkle

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.