Small Spirits

Native American Dolls from the National Museum of the American Indian

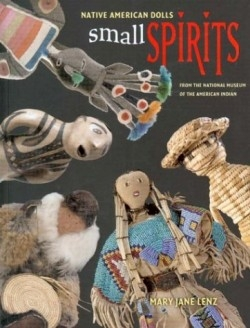

A striking Teton Lakota doll dressed in fringed buckskin, delicately beaded in hues of turquoise and blue, a beaded knife sheath hanging from her belt, and her long double earrings fashioned from porcupine quills, stares out from the cover of this beautifully illustrated and informative volume. It is a revised edition, with all new photography, of the 1986 catalogue, The Stuff of Dreams: Native American Dolls, by the same author, who is a curator at the National Museum of the American Indian. The accompanying exhibit is part of the Window on Collections area of the museums new building on the National Mall.

Lenz opens with a discussion of ancient dolls and their roles as personal amulets or fertility figures. She then categorizes contemporary dolls as those made for play, power, performance, or purchase.

Dolls made for play are found everywhere in the Americas; the museums collection includes a marvelous variety using local materials. There are examples of walrus ivory dolls from the Arctic, cloth and hide dolls from the Plains Indians, and cornhusk dolls from Eastern tribes. Perhaps the most prolific doll makers are the Hopi, who make dolls, or tithu, to represent the spirits, or katsinas, which play such an important part in their lives, and on which all their ceremonies are based.

The uses of dolls for power are related to two ancient concepts: animism and shamanism. Dolls that personify spiritual beings help people deal with forces beyond their control, like illness, or lack of fertility, or food. Dolls used to cure or keep away illness become “repositories of power,” and are highly revered as such. A pair of exquisite Ghost Dance dolls and a paper Otomi doll from Mexico, designed to ensure a good tomato crop, are good catalogue examples illustrating this important function of dolls used for power.

Performance dolls, such as the puppets and marionettes crafted by tribes of the Northwest coast and the Yupik and Inupiat Eskimo communities farther north, often mimicked dancers, who honored the spirits of game animals. Also mimicking dancers are katsina dolls, which help children understand the traditional stories of their ancestors.

Lenz offers a comprehensive discussion of dolls made for purchase, noting that trade dolls existed in the Aztec and Inca Empires long before Europeans arrived in the Americas. Contemporary dolls in the catalogue include a Tohono Oodham basketry doll, highly realistic Eskimo portrait dolls, and numerous katsina dolls, which for years have been included in the annual Santa Fe Indian Market, thus moving into the field of contemporary art.

The “universality” of the dolls displayed in the exhibit and included in this edifying catalogue helps them serve as a bridge between Native and non-Native viewers, as does the dramatic new museum in which they are housed.

Reviewed by

Deborah Donovan

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.