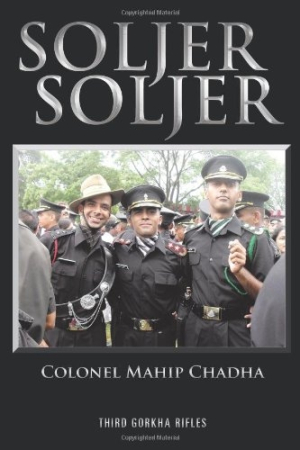

Soljer Soljer

Army life on the frontier, regardless of where that frontier is situated, is much the same today as it was for the legions of Rome or the regiments of the East India Company. It is uniformly dull and boring, enlivened slightly by training maneuvers and war games, and made somewhat bearable only by routine dinners and social gatherings hosted by colonels, generals, and their wives.

Colonel Mahip Chadha spent over thirty years in the Indian Army. This novelized version of his experiences focuses mostly on the rather mundane existence of garrison life, including the challenge of raising a family on army pay and on army bases. “Life moved in its own tranquil manner at Almora,” writes the colonel of the small hill town near the fort where most of the story takes place. This is a region so dull and removed that “one could only become a drunk or an educated lunatic.”

Soljer, Soljer does have a few exciting military moments, however. While the Indian Army has not fought a major war in over forty years, it is on a constant state of alert for terrorists and insurgents who attempt to infiltrate the border from neighboring Pakistan. A few such incidents punctuate the book, and the resulting skirmishes and subsequent casualties serve as serious counterpoints to the otherwise quiet and pacific symphony that is the daily life of a garrison soldier.

There is also a rather spectacular, bloody, and exotic regimental barbecue centered upon the sacrificial slaughter of a water buffalo whose head must be removed with a single stroke lest the regiment suffer bad luck for the coming year. This and other events unique to the traditions of the Indian Army, and, in particular, its Gorkha Rifles Regiment, add spice to what could otherwise be the memoirs of any long-serving officer in almost any peacetime army in history.

Most American and other Western audiences will have difficulty with the colonel’s English. His prose is liberally splattered with Hindi and Punjabi words, titles, and sayings that only fans of Rudyard Kipling and other writers of the former British Raj will comprehend. A glossary of terms or footnotes would have been helpful for those non-Indian readers who are unfamiliar with this and other Anglo-Indian slang which the author uses.

The lack of such explanations in an edition meant for American readers is a serious and sad failing that makes this otherwise fine book far less accessible to any audience outside of India or the Indian community overseas. This failure is all the more surprising as the colonel apparently understands his own limitations on this score, noting after one humorous passage that “such jokes lose their flavour when they are narrated in English—they make you laugh your guts out only when narrated in Punjabi!”

Reviewed by

Mark McLaughlin

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.