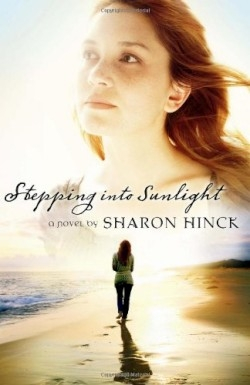

Stepping Into Sunlight

Penny Sullivan teeters on the edge of a chasm. On one side is her life as the wife of a Navy Chaplain and her role as super-mother of a young son; on the other stands a pale wreck, agoraphobic and defeated, clinging to any shred of the person she used to be, now “buried beneath a granite slab of fear.” A trip to a convenience store placed her in the middle of an armed robbery, but the gun aimed at Penny jammed. Though the thief is still at large, Penny pushes the incident aside. She refuses to contact Victim Sup-port, even when her husband is deployed and she is left alone in an unfamiliar town far from family and friends.

Penny attempts to joke her way out of panic in supermarkets: “What’s next, fear of hula hoops?” She compiles a list of tasks: “Join PTA—help out at school. Explore neighborhood.” Yet her efforts to be “the old Penny” by the time her husband returns from his tour of duty fail: “Images flashed around me like lightning. Blood pooling on cold linoleum. A gun swinging in my direction.” She ends up huddled in her closet until her child coaxes her out. At this moment, Penny’s long journey of healing begins.

If this were all the book had to offer, the author’s language and pacing would be enough to carry it forward, but Penny con-fronts not only the fear prompted by her brush with death, she also discovers pockets of shameful judgments she holds about people. A neighbor she dismisses as ignorant teases her out of her shell and Penny both helps and receives help from the woman. A young member of Victim Support, who has multiple piercings and is in therapy for cutting herself to escape deep emotional trauma, touches Penny’s heart. It is at this time that the “old Penny” surfaces, and she shares a project she created for her own healing: “to do something kind for a new person each day.”

The group adopts “Penny’s project.” Her faith in God strengthens; she faces the underlying cause of her col-lapse: her brother had been treated for severe depression and had disappeared over a decade ago. Penny’s greatest terror is that she inherited a strand of DNA that would put her in an institution or on the streets, a fate she fears happened to her brother. Shame accompanies this fear as she wonders why she has not tried harder to find him.

With authority, Hincks, the author of The Secret Life of Becky Miller, depicts how agoraphobia cripples. Penny “hand trims” her lawn rather than venture out to purchase gasoline for her mower. Further, Penny is not her old self when her husband returns. Scars remain, but the new Penny has evolved: “My days had filled with small efforts, sometimes wrenched from the deepest places of my soul, but always guided and supported by God’s hands.”

Reviewed by

Carol Lynn Stewart

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.