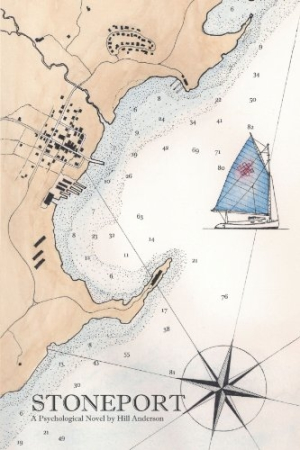

Stoneport

“Wind and water and shoreline can’t be changed. We have to work with the elements as they are.” So writes longtime Buddhist practitioner and social worker Hill Anderson in Stoneport, a sophisticated novel that explores the figurative shorelines, or borders, between men and women, thought and emotion, and truth and fiction.

Intricate without unnecessary complexity, Stoneport weaves several story lines together to create whole cloth. When first introduced, Eli Fox is a young man. Eventually, he becomes an experienced therapist and supervises a bright young doctor named Meagan Rush. The story follows their unorthodox relationship, along with the traumas of the patients they counsel and ground-shaking changes in the field of behavioral medicine itself.

Anderson’s decades of experience is evident in his refined descriptions of his characters’ deepest doubts and highest hopes. His language is precise and evocative. For instance, he summarizes Eli’s childhood memories with lines like, “He remembered his childhood with a sense of defeat and the awareness of a wound that did not bleed.” Anderson’s imagery brings thoughts and emotions vividly to life.

Sea metaphors are central to Anderson’s storytelling, and his tale fittingly moves like a gently bobbing boat in a quiet harbor before he unleashes a storm of conflict. Eli, Meagan, their confused clients, and eccentric colleagues become familiar friends, and then the questions begin. Is Eli and Meagan’s relationship inappropriate? Will its exposure ruin Eli’s career? Are the therapists being forced into unethical treatment methods by the encroaching insurance industry? Anderson skillfully paces the action so that these conflicts almost simultaneously reach peak tension.

Some readers may balk at the academic nature of Anderson’s many intellectual musings, wondering why the line “Romantic cathexis is susceptible to delusion” could not be expressed more simply, as in “love is blind.” His choice allows him to preserve the language and culture of the characters—professional students of human psychology. It also lets him poke a little gentle fun at folks such as himself who have elevated introspection to new heights. One of the most delightful characters, in fact, is the brilliant but single-minded Dr. Nigel Charles, who is feverishly at work on a multivolume publishing project to catalog and cross-reference the entire history of psychological thought.

Although Anderson’s central message is that people should replace controlled patterns of thought with a mindfulness of the present moment, he also suggests that thoughts will live on. Each chapter of Stoneport is, after all, headed by a quotation from future volumes of Charles’s book, circa 2175, showing that humanity will continue to grapple with these issues for a long time to come.

Reviewed by

Sheila M. Trask

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.