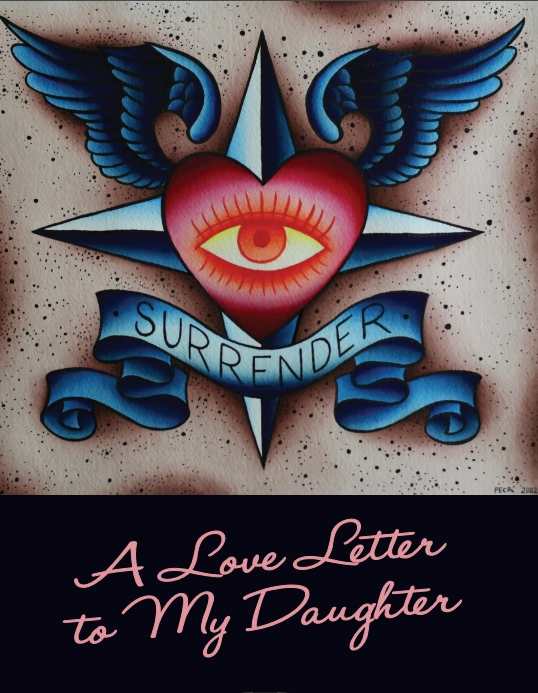

Surrender

A Love Letter to My Daughter

Alpert’s memoir is filled with love and compassion as it confronts the struggles of being a family member to an addict; it suggests a path forward to families under similar duress.

Lou Alpert’s Surrender is a compelling personal account of surviving substance use disorder and recovering, written from the perspective of a family member of a child in active addiction. Alpert’s powerful anecdotes about her own recovery are a source of support for others who struggle with substance use.

As a person in recovery, Alpert knows the Serenity Prayer and has worked the 12 Steps in Al-Anon. Also knowing that people with substance use disorder are often portrayed as hopeless or immoral, Alpert puts a human face on the national drug epidemic through the story of her daughter, Crystal. After seeing Crystal on CNN—homeless, pregnant, and injecting—Alpert realized that she needed to do more for her own sanity and for her children. She knew that a family could recover from addiction, but hadn’t experienced it herself until Crystal was in crisis.

Surrender is both a call to other parents who witness their children’s struggle and a tale that humanizes people in active addiction. Rather that lean into tired tropes about “addicts,” the book portrays Crystal as a whole person. Alpert relates

As her addiction progressed, she carried Narcan to pop people back in case of an overdose. She was a responsible heroin addict. She found a home in the heroin community, where she was respected and admired for her skills. She was a natural.

This image of the “responsible addict” is juxtaposed against stereotypical users. Alpert suggests that, for a remarkable person, a remarkable solution is needed.

Surrender is at turns both frightening and moving. Alpert writes with a gimlet eye, assessing her own relative naiveté about addiction and her total lack of preparedness to deal with advanced substance use disorder. Her descriptions of Crystal’s “paws” are gut-wrenching: her daughter has injected into the veins between her fingers so many times that her fingers had fused. Alpert believed that love and light would help her daughter, but soon learned that actual medical help and treatment were thin on the ground.

Surrender offers neither a melodramatic ending, nor a prescription to end the drug epidemic. The book is, like the experiences of many families of people in recovery, inconclusive. After a long road of many interventions, road trips, pleas, and boundaries, Alpert learned a lot about herself and addiction. Her strength and commitment to help Crystal are apparent. Most of all, Alpert’s understanding of her own codependency, fear, and ignorance distinguish Surrender. Her personal journey is moving because of its honesty: she is neither a martyr, nor a saint—just a mom, doing her best with what she has.

Surrender imparts a unique perspective on a common problem. One in three American households are affected by addiction, and the compassion, tolerance, and love that Alpert offered her daughter are a remarkable example of a road out for other families in duress.

Reviewed by

Claire Foster

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.