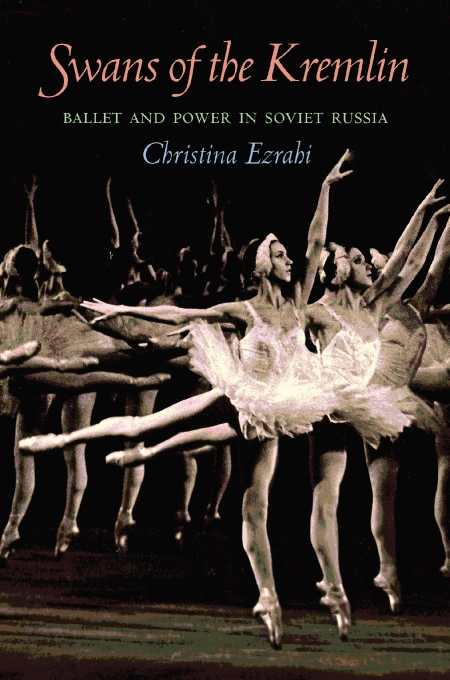

Swans of the Kremlin

Ballet and Power in Soviet Russia

“Art at its greatest is fantastically deceitful and complex.” -Vladimir Nabokov

Nabokov’s belief couldn’t be more evident than in Christina Ezrahi’s Swans of the Kremlin: Ballet and Power in Soviet Russia, a fascinating study of ballet during Russia’s fifty-year Soviet period. From the violence of the October Revolution to the international acclaim under Khrushchev’s Thaw, Russian ballet remained beholden to the art form itself despite the political and ideological constraints routinely forced upon it to support Soviet propaganda.

As dramatic as any of the grand ballets, Ezrahi’s investigation delves into the storied past of Russian ballet as the paragon of choreographic and balletic superiority and as a symbol of cultural supremacy under the Soviet regime. Focusing solely on the ballet companies with imperial status, the Bolshoi and the Kirov (formerly and currently Mariinsky), Ezrahi traces ballet’s dismissal by the Bolsheviks as an art form unable to address the serious issues of Russian life to its rise as the predominant art form of Soviet culture, becoming so ensconced in the international consciousness that Russian ballet became socialism’s ultimate ambassador. Although originally viewed by Lenin as a frivolous art form intended only for tsars and the bourgeoisie, the general public demanded it endure as part of their cultural landscape.

Through painstaking negotiations and strategic compromises, the Kirov and the Bolshoi navigated through the Minister of Culture’s constant demands for Soviet ballets by Soviets about Soviet life, the bureaucratic rejection of formalism, and the insistence that ballet be used as a tool to educate the public and produce the “New Man of the Communist society.” Swans of the Kremlin presents the pivotal moments in both ballet companies in their respective efforts to defend and protect the purity of the art form while also appeasing the mercurial leadership desiring to sovietize ballet by reflecting the Socialist tenets of nationality, ideological content, and party spirit.

Even with the constraints placed on ballet as an art form, Russian ballet managed to emerge with its own definitive style. And during the Bolshoi’s visit to London in 1956, Russian ballet once again asserted that style as one rich in content and with “the emotional absorption and conviction of its technically superb performers.” Ezrahi clearly outlines the national and international importance of the Bolshoi’s international visit, how it solidified the world’s perception of the Russian mastery of ballet, and how the art form ultimately managed to supersede the politics that supported it.

Although Swans of the Kremlin is compelling in its specificity, it is also cluttered in parts and might have been better served by separating the trajectories of each ballet company. Not only for ballet aficionados and history buffs, the author’s effort is a distinguished and intricate view of the intersection of art and politics. In the end, Ezrahi proves that even though art may be political, great art is not only deceitful and complex, but can rise above any ideology.

Reviewed by

Monica Carter

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.