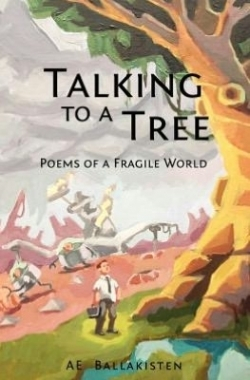

Talking to a Tree

Poems of a Fragile World

South African poet A.E. Ballakisten’s latest collection of poems seethes with rage over the violence humanity inflicts upon itself and the natural world. Hope flickers amid the bleakness via the voices of Desmond Tutu, British nurse Edith Cavell, and the man to whom the volume is dedicated, Nelson Mandela. Ballakisten’s book serves as a call to action, urging readers to stop condoning violence.

The second poem in the volume, “Uncle John,” intends to shock readers out of their complacency. In it, a person speaks to his uncle who claims that violence can never stop; it is simply part of human nature, as told in the Bible. In the last line, Ballakisten writes, “Uncle John was clearly possessed by the devil / so I killed him.” Senseless violence begins the book, and the first of three sections concentrates on the ways in which everyone is complicit in such acts.

In a chilling poem entitled “Flightless Birds,” Ballakisten chronicles the evolution of desert vultures in Afghanistan. With ample carrion from wars, the birds need never fly for food and thus have forgotten how. The metaphoric resonance of the idea is powerful, although the poem itself might benefit from judicious editing, thus allowing the strongest portions to sing. This stands true for much of the book.

In the second section, Ballakisten explores assault on women as well as the hypocrisy of humankind. A prostitute is cruelly abused, women are exploited by the entertainment industry, and ideas of beauty are manipulated. Still, a measure of hope exists among these dark poems. “Giant Tin Can” chronicles a huge old oil tankard at the heart of a village. The speaker’s father tells of its former glory as compared to its present state, “dented and bashed / with holes stabbed all over it / small piercings and large holes / the size of a man’s heart.” The father also adds “that God had put the / giant tin can / there, for us / to store up / all of our hopes.” Though defunct, the can becomes a metaphor for what once was and might be again. This metaphor helps strengthen Ballakisten’s protests without being preachy.

In the final section, the darkness lifts. He suggests this seemingly implausible notion in “Silly Question”: “What if / we were meant to / love each other?” Thus, the book ends on a hopeful note.

As in his last volume, Ballakisten clearly espouses a message, sometimes at the expense of artistry. Still, this collection has stronger imagery, a stronger sense of metaphor, and greater cohesion than his first. For readers interested in international poetry and poetry of protest, Ballakisten offers an interesting example.

Reviewed by

Camille-Yvette Welsch

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.