The Anglo Brambles

A different kind of coming-to-America tale illustrates irrationality of everyday life.

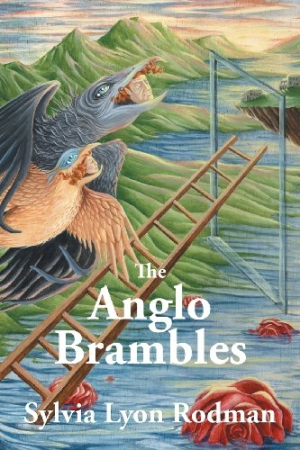

If you’ve ever walked in the woods, you may have seen a bramble—a shrub with prickly, thorny branches. They’re difficult to walk around (much less through) without catching one’s clothes or scratching one’s skin. In many ways, the bramble is the perfect metaphor for anyone emigrating from one country to another: No matter how carefully a person treads, he may get tangled in the bramble. This is one of the several themes of The Anglo Brambles.

The book opens as Doroteo, a wealthy businessman and patriarch of the Buenaventuras, decides to move his family from an unnamed South American country to New York City. That same day, Doroteo, a gruff authoritarian in the eyes of his family, meets his first granddaughter, Nina, who softens his heart. While the rest of the family wonders what’s wrong with him, Doroteo develops a special, lifelong connection with Nina. Her birth and Doroteo’s decision to move mark the start of a journey that will change the lives of everyone in the Buenaventura family.

While The Anglo Brambles is an story about immigrants, it’s unlike most coming-to-America tales. The Buenaventura family is neither poor nor destitute. Polarities—young and old, south and north, new and old, logical and absurd—run as themes throughout the book.

In fact, absurdity sets the tone. While the scenes are mainly realistic, author Sylvia Lyon Rodman has fun with the sometimes irrationality of everyday life. For instance, Doroteo may be transacting business, but sometimes he imagines himself with wings, flying around with Nina.

The tone isn’t set just in the plot. Rodman uses other devices as well, sometimes punctuating her story with amusing footnotes that explain South American culture, expand on a character’s name, or provide other details about a scene.

Rodman also adds her own line drawings. When Doroteo sees a doctor after having heart problems, Rodman shows what the doctor drew (an anatomically correct picture of a heart), what Doroteo sees (a big scribble and nonsense), and what Blanca, his daughter, sees (a grave and a new mourning hat for herself). While the tactic is purely postmodern, the drawings are a humorous counterpoint to Rodman’s prose. And even without these devices, Rodman’s writing crackles with humor.

However, there are times when the author’s phrasing makes her prose overly wordy. At one point, she writes, “Blanca chose to sit down in the darkest spot of the room. She chose to sit in the darkest spot in the room because she doesn’t want to be there. She doesn’t want to be there because …” While the phrasing captures Blanca’s state of mind, the repetitions call the reader’s attention to the writing and out of the scene.

Still, The Anglo Brambles is a novel that is sure to pique the interest of anyone who loves Isabel Allende’s South American epics or the sprawling postmodernist masterpieces of Susanna Clarke or David Foster Wallace. It’s a novel that’s sure to catch readers’ interest as easily as a thorn on a bramble catches cloth.

Reviewed by

Katerie Prior

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.