The Antigone Poems

Like the Greek Antigone, the speaker in Slaight’s poems seems to be crying out to be heard.

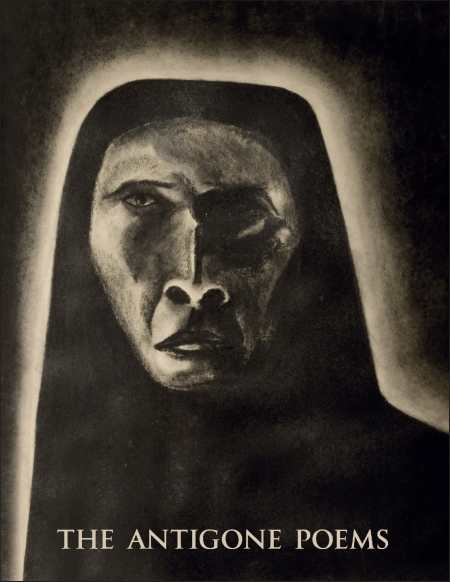

Living in Canada in the 1970s, writer Marie Slaight and artist Terrence Tasker took on timeless themes—birth, death, sexuality—through their art. The fierce poems and dark charcoal drawings from this period are collected here in The Antigone Poems, which uses contemporary language and stark images to express the drama of the Greek myth from which it draws its title.

Slaight gathers her untitled poems into five chapters, each concluding with a somber charcoal drawing by Tasker. While the chapter partitions may have significance to the author, it’s not easy to pinpoint different themes in each section. Rather, Slaight’s poetry uses similar imagery—fire, blood, and raw, savage sexuality—throughout the collection. Tasker’s dark faces, eyeless masks, and shadowy figures are variations on similar themes: thwarted desire, violent longings, and self-expression that risks everything, leaving only an empty husk behind.

Much of this hearkens back to the Greek myth of the title character, Antigone, as told by Sophocles. Born from an incestuous mother-son relationship between Jocasta and Oedipus, Antigone leads a tragic life. She rails against the political powers that won’t let her bury her brother Polynices and ends her days sealed in a cave for the crime of questioning authority. Slaight evokes the myth when she refers to a “daemon ancestry” and exile behind walls of silence in her poems.

Like the Greek Antigone, the speaker in Slaight’s poems seems to be crying out to be heard and is ultimately punished for her efforts. “All is aflame with life desirous,” Slaight writes, “And death submits / To the laughing wild.” Lines like these explore the relationship between birth and death, as played out by the living, breathing, and above all, sensual, human being. Erotic words like “throb” and “thrust” appear frequently alongside “scream” and “spasm,” leaving the reader challenged to work out whether the piece is about the life-giving act of sex or the final agonies of death. Often it appears to be both.

While Slaight’s references to mythology provide a thematic structure, her poems are very evocative of the 1970s. One can imagine her performing these pieces at consciousness-raising group events, her “words sparking from hot entrails” of repressed passion. It was the age of Janov’s Primal Scream therapy, when Slaight’s words—“I walk on blood / I carve a vein / I bear sons / In exile”—might have been encouraged as an emotional bloodletting, crucial to self-healing. Clearly, these themes have long been part of humanity’s story; here Slaight and Tasker add two more voices to the tale.

Reviewed by

Sheila M. Trask

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.