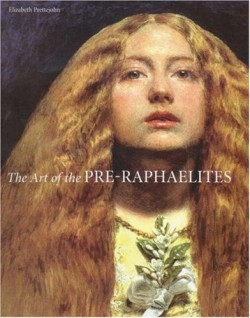

The Art of the Pre-Raphaelites

A statuesque woman draped in midnight blue velvet stands and stretches in front of her embroidery table, surrounded by rich colors and varying textures—the fabric of her dress, the jewels on her belt, the autumn leaves that have fallen on her needlework, the bright stained glass, the rough wooden floor, the polished wooden stool leg, the gleaming silver vases. The painting, by John Everett Millais, entitled Mariana, is a perfect example of the art of the Pre-Raphaelites.

Who were the Pre-Raphaelites, and what was their art like? Prettejohn, associate senior lecturer in Art History at the University of Plymouth, addresses these questions with sensitivity, careful attention, and scholarly expertise in this gorgeous book.

Millais and his friends and fellow painters, Dante Gabriel Rossetti and William Holman Hunt, were frustrated with popular taste in painting, and with the academic precepts of the art world in 1840s London. According to Hunt, they sought to “perfectly revolutionisze [sic] taste.” Toward that end, they formed the “Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood” with a sculptor and three other painters. These men declared allegiance to the style of art of the period preceding the High Renaissance—roughly before 1500—a style considered “primitive” in contrast to Raphael’s maturity.

Prettejohn writes: “Pre-Raphaelite painting technique was simultaneously very old, in its attempted return to the methods of the first oil painters, and utterly novel, since those methods were ‘scientifically’ examined for the first time.”

Other painters soon adopted the style. Artists without standard training, especially women, who were denied entrance to art schools, found advantages in the Brotherhood’s rejection of academia.

These painters portrayed people and nature with perfect truthfulness, rendering every square inch of the canvas in exacting detail, rather than clearly portraying principal forms in the foreground with shadowed, indistinct backgrounds. In Hunt’s Valentine Rescuing Sylvia from Proteus, every blade of grass is articulated; each separate link in the hero’s chain mail can be counted; one can even discern the expressions on faces in the distance.

Prettejohn examines this art with the minute attention one must pay to each painting in order to absorb all those details. She analyzes the style’s visual aesthetic, its place in the history of art and society, and its portrayal of women. She draws on—and graciously acknowledges—a wide body of scholarly work. The book is beautifully laid out, with vivid color plates clearly marked and juxtaposed conveniently with the text that refers to them.

The author argues that Pre-Raphaelite art requires long, close scrutiny. Her book equally merits lingering and absorbing attention.

Reviewed by

Karen McCarthy

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.