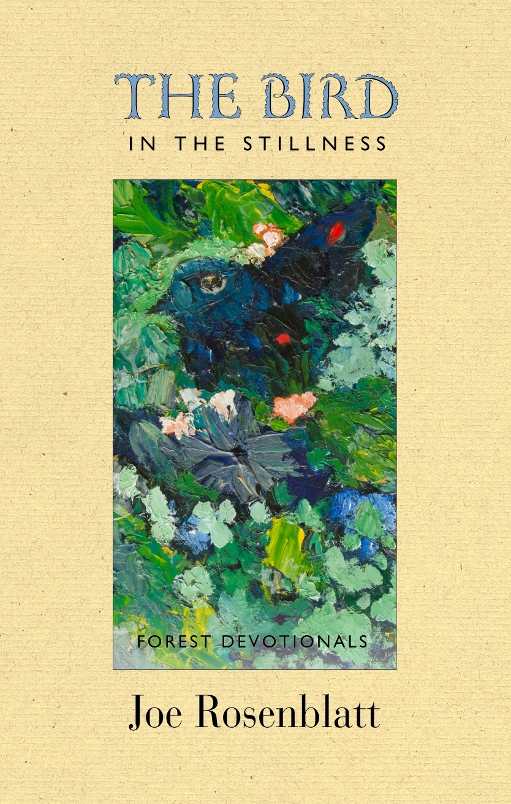

The Bird in the Stillness

Forest Devotionals

This collection of poetry soars above, like the trees in the forest that inspired it.

For anyone who’s ever pondered the secret life of a forest or aspired to be an unseen observer among the trees, Joe Rosenblatt’s poetry collection The Bird in the Stillness: Forest Devotionals will prove both illuminating and delightful.

In many of these poems, the Green Man, a kind of forest deity invoked by Rosenblatt, is referenced. The Green Man is part guide and part alter ego, an object of study and the holder of a foreign point of view that the poems’ narrator attempts to interpret. Anthropomorphism isn’t quite the right word for this technique, which provides glimpses and fragments of the Green Man—his branches intertwining with those of other trees, reminiscent of humans holding hands—but never fully revealing him, and maintaining the sense of a mystery unsolved.

Through this lens, Rosenblatt captures the utter alienness of the forest and demonstrates that, despite our dependence and proximity, we are no longer its natural inhabitants. All of the Green Man poems, which comprise roughly eighty pages, are written in sonnet form, though rhyme is nearly absent and meter varies. This form is well chosen—the sonnet is a sturdy container for Rosenblatt’s remarkable powers of observation and imagination while providing him the freedom to stray within the its limits. The occasional repetition of certain terms—“mucilage,” “foliated,” and of course, “Green Man,” as well as less-vegetational Rosenblatt favorites like “noggin” and “nibbled”—give a sense of consistency, in voice and theme.

Rosenblatt covers a great spectrum of emotion, from the dark reflections of “Viewing a Midday Lunch”—“In these woods even dreams are eaten by a slim garter snake. / I and the Green Man know: Life makes a meal of the living”—to the lighter tone of “Photosynthesis Motel,” with its humorous wordplay and conceit—that the Green Man should find a Green Woman as his overnight companion:

Attired in wild fern, salal, and moss of emerald green

they’re greeted by a puffball at a seedy reception desk.

These poems read as variations on a theme, with a cumulative effect; each poem takes the reader deeper into the forest and immerses a bit more in its world.

Though there is no official line of demarcation, there is a shift in the book’s final twenty pages, which step away from the Green Man motif. While many still focus on nature, these poems, including the title poem, take a greater variety of forms, with several references to Ken Kirkby, a landscape painter who presumably accompanied Rosenblatt on some of his outings. Rosenblatt’s sense of humor is again evident in the book’s final poem, “What’s on Tap?,” but these poems prove less satisfying, if only because they abandon the deeply hypnotic effect Rosenblatt creates to that point.

Rosenblatt’s black-and-white ink illustrations appear occasionally among the poems, a nice addition for the visually inclined. The Bird in the Stillness soars above, like the trees in the forest that inspired it.

Reviewed by

Peter Dabbene

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.