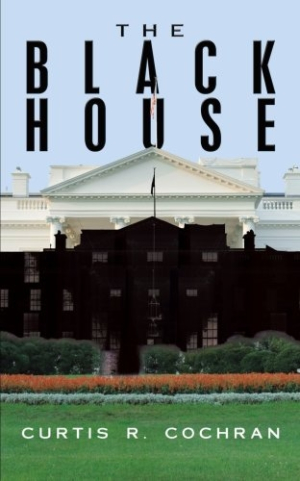

The Black House

Curtis R. Cochran crafts a work of prophetic historical fiction in his novel The Black House. The story begins at the end of 1982, with the first chapter introducing October, “a young man in his early thirties reach[ing] out for the impossible dream … unity of Black America.”

Readers see right off the bat that Cochran is taking on very relevant racial and political themes. October acts out Cochran’s beliefs: that races will be united when the rule of God supersedes the rule of government. As October sets out from New Orleans—which is also Cochran’s home town—he meets Little Adderly, a troubled youth who compels October to action. He also gives deeper meaning to the establishment of the mysterious Black House: “The Black House is the gate of opportunity for blacks as a nation, and whosoever or whatsoever stands in its way will be consumed.”

Life gets more and more complicated for October as the book goes on. He struggles to find a way to live out his faith in God and his beliefs about society in a way that will create true change. Many idealistic readers will feel October’s angst and frustration. However, they won’t feel a deep connection to October himself because the matter-of-fact, summary-style writing makes him seem more like a collection of ideas than a person. Cochran’s story takes on a cautionary tone when October is charged with murder; Cochran’s message to readers seems to be that meaningful change is not welcomed. The narrative also draws on Cochran’s military experience. October and his followers’ idealistic fight ends tragically, but there is hope for rejuvenation of their efforts even in the wake of despair.

Cochran’s novel struggles to clearly convey his society-changing ideas. The book’s sentences and ideas are difficult to follow and laboriously written, and the plot follows suit. Readers will often be confused about what is going on. Numerous punctuation errors, like misplaced quotation marks, make meaning unclear. The dialogue is also muddled because it is difficult to tell when speakers shift, and the characters talk almost as if they are reading from a textbook rather than having a conversation with another person. The continual use of present tense is wearying: “He arrives at the airport and bids his driver farewell. Now he is boarding the plane headed for St. Louis.” These issues along with the flatness of the characters will leave readers desiring more from this book.

For all its pointed, potentially radical themes, The Black House is neither racist (though it is racially charged) nor anarchist (though it does throw some hefty challenges the government’s way). Cochran’s hope for eliminating racial disparity is for the good of all of humanity. His novel will appeal most to readers whose idealism makes them chafe at the restrictions racial inequality places on all people.

Reviewed by

Melissa Wuske

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.