The Burning World

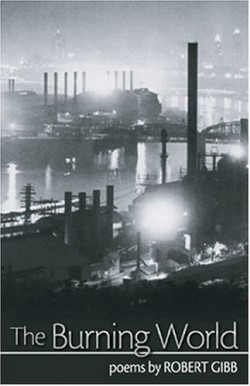

For this poet, heaven is gray, industrial, and mechanized, and around every corner of this Burning World, there is some residue of what is left behind—ash, slag, pig iron, and Gibb himself, a child who shared the world with his mother for a mere twenty days. From this early loss, which Gibb describes as his first, comes the book’s prime directive: he writes in “First Visit to My Mother’s Grave, North Side Catholic Cemetery”: “The dead are raised up / In sorrow, and in language alone.” It is to the language, the elegy, that Gibb is looking.

Gibb, the author of five previous books and recipient of numerous awards, an NEA grant and a Pushcart Prize among them, remains a poet of place, locating himself and his poetry firmly in Homestead, Pennsylvania, just outside of Pittsburgh. Like its neighbor, Homestead is a steel town, still alive after its principal industry has gone, “a world where work is sacramental.” Akin to B. H. Fairchild’s machine shops and blue-collar heroes, Gibb’s steel workers live amid the knowledge that anything might take them, and the chronicles of death are long: an uncle dying in his chair, a grandfather on the floor of the steel, a mother crying out to her husband the night she passes. Gibb makes from these losses a book of elegy that mourns the passage of both the people of his life, and the town Homestead once was.

Gibb punctuates the book with poems that refer to photographs by Lewis Hine, and the selection of kindred spirit is apt. Like Hine, Gibb focuses in tight to his subject, giving readers a tableau made startling by the details within it. Both place their subjects in the belly of some work hell and both know not only how to tell a story, but how to allow a detail to tell a story. Gibb describes his parents’ wedding photos: “Their lives like the fur rippling on her stole.” He writes of his uncle’s cigar: “Uncle Arch, watching him roll // a Punch Havana before the blue flame / of his match, intoning tobacco / in small quick puffs as the lit end // Caught and coaled, and I could watch / The faint white rime of ashes / Taking hold, like a papery spume.”

This finely crafted language, formal intent, and careful consideration typifies Gibb’s poems. The articulation of place gains its power from the contrasts, light and dark, the investment of emotion, and the loss of loved ones. For fans of Fairchild and Philip Levine, Gibb offers another entrée into the grayscale world of working-class towns and the families that live in them.

Reviewed by

Camille-Yvette Welsch

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.