The Canary Room

A Novel

Inner monologues with a noteworthy stream-of-consciousness style trace the coming of age of a foster child during World War II.

In their debut novel, The Canary Room, set in 1945 Idaho, Edwin F. and Linda Casebeer create a vivid wartime backdrop for the story of a twelve-year-old boy in an unstable family situation. Based in part on Edwin’s childhood, the novel is rich with animal imagery and period slang. The book is written with a novel, virtuoso style, punctuated by flashbacks and stream-of-consciousness passages.

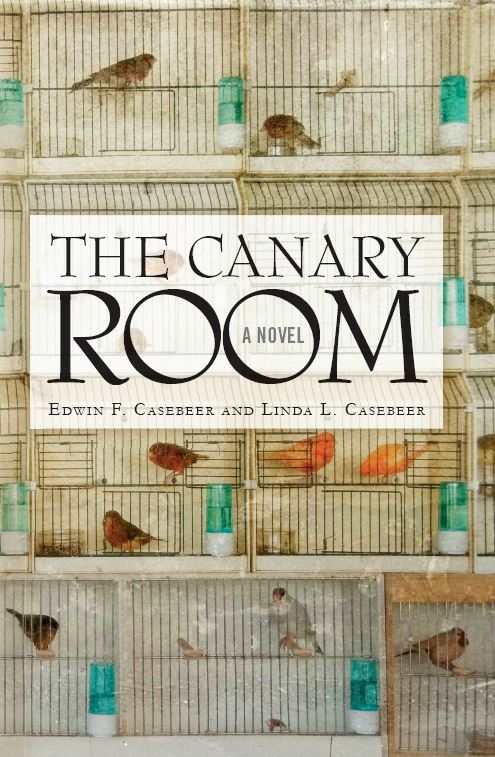

Young Herman Auerbach has had a tumultuous upbringing. After his parents’ divorce and a bout with polio, Hermy lives first with his Auntie Ide and later with foster families. His foster mother, Gladys Williams, keeps dozens of canaries, a welcome animal presence for a boy who grew up with pet snakes and rats. Parallel structures allow comparison of Hermy’s current idyllic childhood with often traumatic events from his last few years. His thoughts and memories pervade the narrative, and World War II is a constant background hum.

The Casebeers’ prose is often impressive, with short but lyrical phrasing. The first page, especially, has memorable descriptions: “At the foot of his cot, canaries boxed and hutched, cages shaped in minarets and domes, wood, rusty iron, gold, silver…Cages of canaries, coral, orange, white, yellow wings striped tar black, flutter and hop, flap and clatter.” Canaries and snakes, recurring motifs in the novel, are opposing metaphors that suggest innocence and experience. Hermy’s snake tattoo, for instance, is a worrisome sign that he has grown up too fast, and his attempt to start a snake zoo seems to foreshadow disaster.

The novel sets up a lucid contrast between Hermy’s seemingly all-American boyhood with the Williams family and his disturbing past. His new life is full of baseball, fishing, and canoeing with his foster siblings, whereas his dark history surfaces in details such as his smoking habit and the scar from a gunshot wound inflicted by a drunken uncle. His parents’ divorce, an uncle’s death, bullying, and hints of sexual abuse all add up to make Hermy seem much older than twelve, while the evocative wartime setting exposes harsh realities of rationing and the draft.

The typesetting distinguishes the past from the present, and internal dialogue from real life: Hermy’s thoughts are in bold, flashbacks are in italics, and past thoughts are in bold italics. At times, this strategy seems overcomplicated and makes the narrative feel fragmented, yet it allows for clever parallels. For example, while eating a venison dinner, Hermy recalls getting fish and chips in Seattle; while playing a coin game with Sonny Williams, he remembers playing it with a Japanese friend. Hermy’s inner monologues adopt a noteworthy stream-of-consciousness style: “Silently. Like an Indian. Like the last of the Mohicans.”

Hermy’s thoughts and the dialogue are full of convincing slang, such as, “I wonder who started calling [Idaho’s capital] boy-zee? Some dumb sourdough silver miner from New York, I bet.” Strong female characters include Mrs. Williams and her daughter Helen, who’s in the army; fortune-teller Rose; and Hermy’s cousin, Iris. Ending abruptly with the Hiroshima bomb-drop suggests the Casebeers may be pondering a sequel.

A well-written coming-of-age tale, The Canary Room will appeal to fans of John Irving’s and Don DeLillo’s works.

Reviewed by

Rebecca Foster

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.