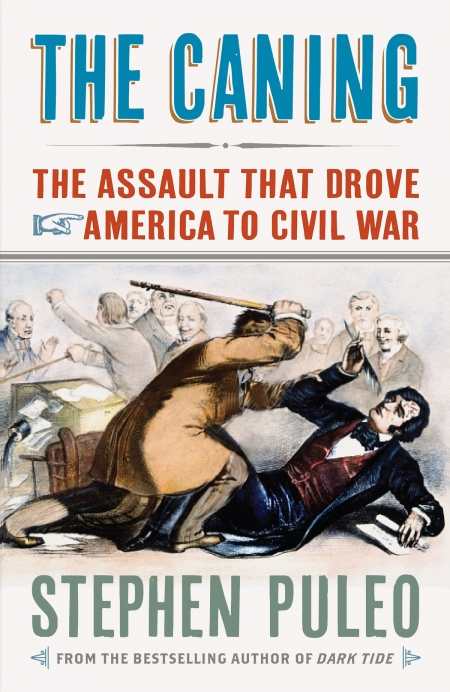

The Caning

The Assault That Drove America to Civil War

When Congress passed the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, a bill that allowed slavery to extend into the western territories by popular sovereignty, Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts seethed in outrage, fearful that Kansas would enter the Union as a slave state. By 1856, “sectional strife, assaults, barbarism, and mayhem … rocked the territory” as proslavery Southerners and antislavery Northerners vied for dominance. The hostility, Sumner concluded, caused the nation to “shake with the first throes of civil war.” As an uncompromising abolitionist and “the country’s most eloquent and powerful antislavery voice,” Sumner was duty-bound to take action.

Speaking from the US Senate chamber on May 19, 1856, Sumner delivered “The Crime Against Kansas,” a fierce and controversial speech intended to “enrage and inflame” the Southern slave power—in particular, South Carolina—and denounce its violent intimidation of the territory’s citizens who opposed slavery. Sumner’s allies praised his oration as “majestic, elegant, and crushing”; his critics thought it “obscene and vulgar,” “un-American and unpatriotic.”

Representative Preston Brooks of South Carolina found Sumner’s speech personally offensive. In addition to insulting Brooks’s home state, Sumner pilloried the representative’s stroke-affected cousin, Senator Andrew Butler. Brooks, a proslavery defender of the Southern way of life, decided Sumner deserved to be punished for his injurious and inflammatory rhetoric. Thus, on May 22, Brooks entered the Senate chamber and beat Sumner about the head with the gold-tipped end of his cane. After the thrashing, Brooks walked away, leaving Sumner bloodied and unconscious on the Senate floor.

As Stephen Puleo relates in this gripping, richly detailed, and well-written account of nineteenth-century America on the cusp of Civil War, the caning of Charles Sumner was an act of unparalleled brutality, a shocking breach of decorum, and the defining moment when North and South recognized “they could no longer rationally discuss their sharp differences of opinion regarding slavery.”

Puleo’s comprehensive chronicle outlines the “domino effect” of the period’s other portentous events—the Compromise of 1850; the Fugitive Slave Law; John Brown’s raid at Harpers Ferry; the Dred Scott Supreme Court case; the rise of the antislavery Republican Party; the election of Abraham Lincoln to the presidency in 1860—and shows with mastery how these measures conspired to dissolve the Union. Additionally, Puleo’s compelling specifics about the extent of Sumner’s injuries and his two-and-a-half-year convalescence impart solemnity to an assault that’s been reduced to banality.

Puleo concedes that much has been written about the caning and Charles Sumner. Yet, what makes Puleo’s narrative distinctive is his insightful biographies of both Sumner and Brooks. Puleo strips away the “stereotypical cliché[s]” of Sumner as a righteous, victimized statesman and Brooks as a bullying, unprincipled ruffian.

Throughout The Caning, Puleo’s prose is expressive, yet straightforward. His skillful transitions from scene to scene as well as from Northern to Southern viewpoints make for lively storytelling. Puleo has created an enlightening, significant, and commendable contribution to the annals of American history.

Reviewed by

Amy O'Loughlin

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.