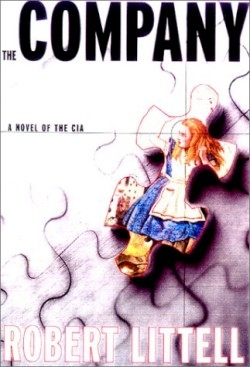

The Company

A Novel of the CI

Here is a dazzling exploration of espionage—“the

art of the possible” in “a wilderness of mirrors.” The narrative surges forward from the peril-fraught Berlin of the 1950s through the doomed Hungarian Uprising, the botched Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961, and Russia’s disastrous Afghanistan campaign during the ’80s, to the cliff-hanger anti-Gorbachev putsch attempt of 1991. Presidents of the U.S. and Soviet Union, as well as CIA chiefs and traitors, fuel the action. The hard-drinking, gun-toting Harvey Torriti (“the Sorcerer”) heads the Berlin station, recreating his inimitable real-life original, William Harvey.

Through Torriti and his “Sorcerer’s Apprentice”—the newly recruited Yale graduate Jack McAuliffe—the author plays out his major theme: the failed exfiltration of a would-be defector, which indicates a mole in the CIA network. Torriti’s efforts to unearth the mole demonstrate on-site spycraft at its best; those of counter-intelligence chief James Jesus Angleton show off-site cerebration at an agency-crippling worst. In tracking the careers of McAuliffe and his two college friends, Littell explores love and loyalty, abandonment and betrayal. Locales (Berlin, Budapest, Moscow, Cuba, and particularly Afghanistan) are grippingly drawn, with a pervasive fear of set-up, exposure, and capture. Every event is loaded: “In our line of work,” said Torriti, “coincidences don’t exist.”

Littell blows open the hidden worlds of the KGB, Mossad, and MI6, all prone to the cancerous power of disinformation. Equally incisive in depicting agents and moles, he strips away facades to reveal just what makes people sustain or betray causes at the risk of honor, family, and life-and to what benefit.

Constant tension gives The Company its cutting edge: Littell perfectly captures the obsession and guilt-often misguided-central to careers and collapses in espionage. Strait-laced Angleton, endlessly cross-referencing a mountain of mole-tracking files, slides into paranoia; Starik, the visionary, sexually corrupt Russian mole-handler, sinks into senility believing he could destroy the U.S.A through economic sabotage. Both shared the ideologue’s terrifying isolation. Wrenchingly shown are the private hells that followed the failure of the Hungarian Uprising, the Bay of Pigs fiasco, and the (un)necessary sacrifice of agents.

Washington D.C.‘s electric supplier, Starik’s birthplace and hidden Berlin presence, and the ephemeral Donna’s fate will puzzle keen readers; Amy Knight’s Spies Without Cloaks and Trento’s The Secret History of the CIA will reward industrious ones; and Littell’s fourteen previous books will delight all newcomers. A writer who can happily use “hypogean,” appositely quote Greek historians, and on a single page alert readers to the brilliant Sándor Petöfi, Karinthy Frigyes, and Attila József deserves generous thanks.

Reviewed by

Peter Skinner

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.