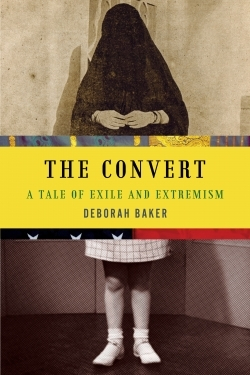

The Convert

A Parable of Islam and America

America in the late 1950s and early 1960s wasn’t an easy place or time for a “misfit” to come of age. Margaret Marcus was an unpretty, unpopular, and very bright Jewish girl growing up in suburban New York, in an era that clung fast to its postwar claim on “normalcy.” While her classmates were gossiping, Margaret was writing and publishing tracts against modernization and secularization. Her keen interest in history and politics—especially her empathy for the Palestinian cause—and her lack of attention to her own appearance and sexuality infuriated her family and the therapists they consulted; Margaret was committed to a mental institution for six months.

By the summer of 1962, the young woman from Westchester County had become Maryam Jameelah, a Muslim living in Pakistan, in the home of the man who ultimately laid the intellectual foundation for militant Islam. Biographer Deborah Baker suggests that extremism was Jameelah’s solution to the complexity of her own sensitive, provocative nature and tries to find out why in The Convert.

The author’s insertion of herself and her investigation into the book are such that she is a significant character in the story’s unfolding, a device that may not be to every reader’s liking. What Baker conveys, however, is an honest attempt to know her subject without preconceptions or resorting to pat representations of complex issues. A former Pulitzer-Prize nominee, her method suggests that there’s more than one way to approach a biographical study and that one’s subject is perhaps the ideal force to provide direction.

As Baker questions everything she encounters about Jameelah, she invites the reader to do the same. What does it mean, for instance, that “Peggy’s” chatty letters home to her parents, written from Pakistan and archived at The New York Public Library, are so different from the uncompromising tone of her anti-Western articles published during the same time? These letters form the backbone of Baker’s quest, and just as her subject is revealed to be multi-dimensional, so the faith she exiles herself to pursue surfaces in numerous iterations.

Two-thirds of the way through The Convert we learn another, contradictory account of Maryam’s early months in Pakistan, that of the son of her mentor, Mawlana Abdul Al Mawdudi. When it occurs to Baker that the credibility of her primary source may be in question, this knowledge initiates a more classical mystery-style plot, which actually helps to unpack the labyrinthine issue at the heart of the book: our perceptions of the very nature of God as it intersects our own human natures.

The specter of 9/11, of course, haunts The Convert throughout. And it’s a satisfying moment when Baker asks Jameelah if she feels responsible in any way for radicalizing Muslim youth. But, in keeping with the author’s self-referential discourse throughout, we are by then conditioned to ask ourselves about our own expectations for such a moment, and what they may say about us

Reviewed by

Julie Eakin

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.