The Daughter of L'arsenal

“No one at L’Arsenal ever had to pay taxes. We had no roads, electricity, running water, or sewer facilities,” the author writes about her home town, a rural community on the outskirts of Cayes in southern Haiti.

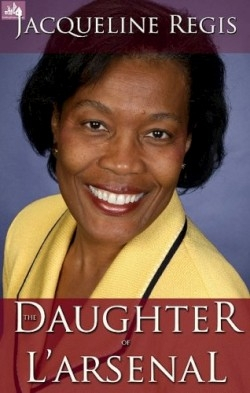

In The Daughter of L’Arsenal, Jacqueline Regis, a former state assistant attorney general, the “first black woman president of one of the largest American women bar associations,” and currently a corporate lawyer, recounts her life from her disadvantaged childhood in hurricane-vulnerable Haiti to her career in the United States.

The author describes her mother’s youth and the “web of misguided social values” embraced by her family. Mama survived her asylumesque existence and became a source of inspiration to her daughter. Regis thanks her devout Catholic mother for “two essential blessings”: devotion to her and “relentless determination” to see her educated. She lives by her mother’s words: “The only responsibility you have is to give your best effort to whatever task is placed in front of you today—the rest will take care of itself.”

Regis tells of her Mary and Joseph-like birth in an “abandoned hut.” From there she becomes a raconteur of childhood memories with cultural accents. Vignettes include her mother’s sugarcane harvesting, scarecrowing rice fields by screaming to tourterelles (small birds), speculation about whether neighbor Leon deposited a murdered man’s body in the school’s outhouse, “invisible hands” that stole a red hen, dancing with her own shadow, a prankster’s skinning of her pet sheep, and being occasionally left at Elise’s prison of a household.

In 1970, after her schooling in Haiti, the author joined her mother who had immigrated to New York City. Regis lived with a caring couple in Connecticut, and in exchange for an education at Greenwich High School, worked as a mother’s helper and taught French to their children. She later graduated from Principia College and moved to Boston. There she worked full time while earning a Juris Doctorate from Suffolk University. Of special note are Regis’s thoughts on her years of social loneliness and cultural isolation.

The book reads like a fast-paced novel due to detailed anecdotes in short chapters. The author has a panache for turning phrases, such as “slicing words,” “pregnant moon,” and Elise always wearing “puritanical black.” Improvement could have been made by using a cover image that reflects the author’s journey, adding an explanatory subtitle and a contents page to serve as a narrative outline, editing redundancies, and including fewer genealogical tangents.

This memoir is a testament to prayer, perseverance, and the principles of a loving mother. Immigrants from low beginnings will find the book especially inspirational.

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.