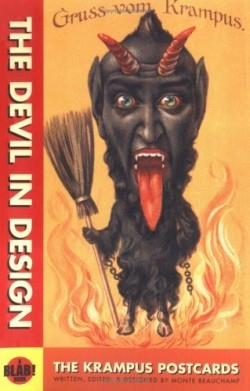

The Devil in Design

The Krampus Postcards

Christmas is a time of peace and good will, happy children and kindly adults, presided over by a merry old gent in red with a staff of flying reindeer and toy-building elves. In America, that’s been the case for the last century and a half, more or less, but in other parts of the world Christmas has its darker side. In England, ghost stories around the Christmas hearth are the tradition. In Germany, Poland, and other European countries, St. Nicholas, or Nikolaus, as he is known there, visits the homes of children accompanied by some pretty sinister denizens of the otherworld. Chief among these, at least in some regions, is the Krampus, who takes care of the “naughty” category on Santa’s twice-checked list.

What is the Krampus? Beauchamp’s book exhibits a wide variety of portraits of this devilish character, who in European tradition accompanies St. Nick on his annual rounds on December 6, St. Nikolaus Day, and does more than put coal into the stockings of the badly behaved. Says Beauchamp, “In European folklore, the Krampus is [St.] Nikolaus’s dark servant…a hairy, horned, supernatural beast [with] pointed ears and long slithering tongue [who] terrorized the bad until they promised to be good. Some he spanked. Others he whipped. And some he shackled, stuffed into his large wooden basket, then hurled into the flames of Hell!” The Krampus looks, in fact, like the Devil himself, complete with hairy legs, a single cloven hoof (the other foot is a foot, although often depicted with long talons for toenails), and a long tasseled tail. He carries a birch switch, to beat his victims, and long lengths of chain and shackles.

Unaccountably, the Krampus became wildly popular as a subject for penny postcards, particularly around 1898-1914—when postcards were flourishing, chromolithography allowed magnificent color to entice ever-greater efforts from artists, and Christmas as a favorite subject prevailed in the marketplace. The visually arresting images of the Krampus graced great numbers of these cards, and the selections Beauchamp has included in this book, “rare examples” that have survived the years, are nothing short of stunning.

Anonymous artists seem to have thrown their best efforts into these magnificent images. Colors are liberally used, with lots of red as one might expect of holiday cards. Yet color is not the only attention-getter about these images, nor is the gold trim frequently used to embellish them. Often disturbing and frightening, always beguiling, and sometimes slyly witty, the Krampus rides, walks, drives a sleigh or a motor car, or jumps off cliffs and into flames with a woven basket on his back filled with crying children or fearful adults—or drags these same victims along behind him in ropes or chains. He bursts into houses and drags children and adults along by their hair, or frightens them into saying their prayers, or boils them in cauldrons over leaping flames; he seems to flirt with an older woman on a park bench or younger women captive in his basket; he cavorts with three young and scantily clad young women clinging to his back (while dressed like a gentleman in a pinstripe suit, complete with monocle and top hat); and in the guise of an elegantly dressed woman, reaches out to add a young reprobate to her basket.

The variety of depictions is as startling as the excellence of the artistry. In one, a lovely woman, dressed in Gibson-girl style, sits astride a flying broomstick (perhaps an enlarged birch switch), holding the broom bindings as if they were reins. Krampus, with rich irony, rides sidesaddle behind her, gazing adoringly at her. Another shows a train, drawn by a fearsome winged dragon breathing fire; the card proclaims it the “express train to Hell.” The lead car is inscribed in German as the office of Krampus; the next two are designated “bad boys” and “bad girls.” On the platform wait a throng of crying, fearful children; Krampus is dressed as a circus ringmaster.

The book is printed on good weight stock, and the color is lush and rich. Commentaries on the origin of Krampus himself, a brief history of postcards, and the custom of dressing up as Krampus in Austria during the Christmas holidays are printed in white on red two-page spreads; those and the introduction are the only text in the book, with the rest devoted to these compelling images, many annotated in a variety of languages. As a commentary on the dark side of the most joyous of holidays, Devil is well worth close examination.

Reviewed by

Marlene Satter

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.