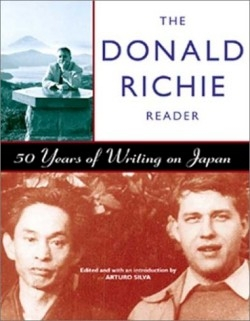

The Donald Richie Reader

50 Years of Writing on Japan

The night was dark, the village small. The young men jostled each other as they made their way into the Shinto shrine, pressing together so tightly that the entire mass of humanity hovered a few feet above the ground. The Festival of Darkness passed quietly, according to Donald Richie, the one Caucasian among the Japanese.

Richie first came to Japan as a member of the Occupation in the wake of World War II and eventually settled there, returning to the United States only occasionally. Over the course of fifty years, Richie created a vast number of writings, ranging from weekly book reviews for the Japan Times to his masterpiece work on Japanese film, Ozu.

In this anthology, Silva, himself a former longtime resident of Japan, sifted through Richie’s published and unpublished writings and selected compelling representative excerpts. Silva has chosen a good balance of Richie’s professional writing and personal observations, arranged by such topics as “Film,” “Fiction,” and “People.”

The collection opens with Richie’s telling of how he came to be in Japan, his desire to leave small-town America, his feelings of being obviously foreign in an occupied land. In an early piece, he describes how he had to sneak into the back of Japanese movie theaters during the Occupation; as the American forces withdrew, and as Richie gained a reputation as an expert on Japanese film, he enjoyed private screenings and close relationships with the likes of Akira Kurosawa and Yasujiro Ozu.

Richie’s fiction vividly evokes Japanese life. In “The Stone Cat,” an unnamed narrator struggles with making the residents of a tiny fishing village understand his desire to see a local monument. Another story, “Commuting,” describes a young Japanese man’s ill-fated romance with a fellow commuter on a crowded train.

Some of the more subject-specific writing might be slow going for readers looking for a general sketch of Japan. For example, Silva chose ample selections for the “Film” section; however, the pieces require a hefty knowledge of Japanese film from the mid-century to be fully appreciated.

Richie is no B.F. Pinkerton; his writing is akin to Pico Iyer’s in The Lady and the Monk, another keen observation of Japan. Though Richie himself is contemptuous of the weary expatriate who mourns for the past, his later writings evoke a “lost Japan.” Richie’s love for his adopted country is unfaltering and present throughout this work.

Reviewed by

Johanna Massé

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.