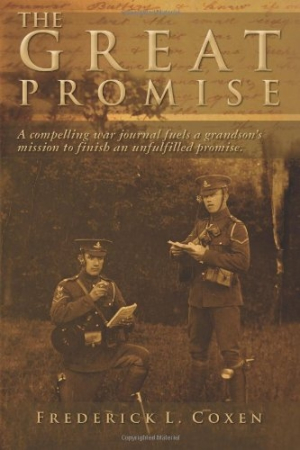

The Great Promise

Frederick L. Coxen’s life was changed when he stumbled upon his late grandfather’s journal from World War I. Coxen did more than just transcribe the worn, weathered diary and annotate it with maps and a historical narrative to create this volume. He devoted years attempting to fulfill the terms of a pact his grandfather had made with three fellow soldiers in the summer of 1914—an unkept pledge that, to his dying day, haunted the elder Coxen.

The Great Promise is thus a primary source, a history, and a personal quest. Coxen’s grandfather (also named Frederick Coxen) was called to the colors to serve in the Royal Field Artillery. He was among the first British soldiers to land in France at the start of The Great War, and he fought in every major engagement until being gassed in 1915. The journal covers his first year at the front almost day by day. His reports, observations, emotional asides, musings, and even occasional jokes lure the reader into a fascinating, detailed, and very human time capsule.

To assist those unfamiliar with the period, the younger Coxen intersperses his grandfather’s entries with short but clear passages explaining the commanders, maneuvers, and terminology of the First World War. His simple, clean maps show the routes his ancestor trod and the towns he fought over. These help set the stage for his grandfather’s wonderful and rarely hurried prose.

There are episodes of unconscionable horror, such as the crucifixion of captured soldiers (by both sides) and reflections on the deaths of friends and enemies alike. Upon seeing one man fall, for example, the elder Coxen writes, “I wondered if this means the breaking of a woman’s heart, or had he little children?” There are also warm moments, such as when soldiers share their already meager rations with starving refugee children, and bits of very British pluck, notably of how “nothing short of an earthquake would make us miss our tea time.” The journal entries allow the reader to follow one of many green young men as he matures within months into a war-weary veteran.

While his ancestor’s words and experiences are the true stars of the text, there is a second story here, one told almost as an afterthought in the last twenty pages of an already slim book. The elder Coxen and three comrades made a pact that if any of them fell, the survivors would visit the deceased soldier’s family, relate the story of his passing, and offer comfort. Coxen saw all three of his mates die, even holding one of them in his arms as he expired. Yet, he never made good on his part of the bargain.

As he laments in an entry made in another journal in 1945, when living in America and writing during a second war, those old comrades continued to haunt Coxen’s dreams, asking if he would ever fulfill that great promise. How his grandson sought to made good on Coxen’s word, and the detective efforts he undertook to find the descendants of those dead soldiers, is a short but engrossing and very moving story, and one well told by the author in his final chapter.

Reviewed by

Mark McLaughlin

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book and paid a small fee to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. Foreword Reviews and Clarion Reviews make no guarantee that the publisher will receive a positive review. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.